Unless you’re independently wealthy, “following your passion” can be costly

MANDEL NGAN/AFP/GettyImages

MANDEL NGAN/AFP/GettyImages

When orchestra conductor Daniel Hege addressed the Bethel College graduates in Kansas this May, his message was simple: “You owe it to yourself and to others to follow your passion — and by doing so, you will give others around you, and the world, something significant.”

A similar message was given to Stanford University grads in June, when Katharine Jefferts Schori, the former heard of the Episcopal Church, told them that “our own willingness to invest our full selves in a passionate dream … is perhaps the most worthy use of one’s life.”

This kind of advice — to “follow your passion” at almost all costs, in both your career and life — was given to graduates throughout the country. And the term “follow your passion” is now appearing in in more books, particularly those focused on careers, and Google searches on the topic are higher than ever before.

After a snorkeling trip to Hawaii during high school, San Diego resident Deborah Fox became fascinated with marine biology, which she subsequently majored in. So when she landed a job at a fish farm upon graduation, she was thrilled — but not for long.

“I was throwing fish chow into the tanks and the fish were going crazy, splashing around and soaking me. Here I am a social person and I’m alone all day with these fish who just splash me with water. What am I doing?” she asked herself. “I found out that having a passion for a certain type of study or interest does not necessarily translate into finding passion for the day-to-day work in that area,” she says.

Career coaches say the same. “You may be passionate about the idea of a career, not the career itself,” says Cheryl Palmer, the founder and a career coach at Call To Career. And, like Fox did, you may find that your personality traits — in her case, a love of people — don’t fit in with the traits needed to do your job.

That’s one reason that Darrell Gurney, the founder of career site CareerGuy.com, says that, before you pursue a certain line of work you think you’re passionate about, you should ask people who have worked in the field a long time about what the job is like, and its pros and cons. Palmer recommends shadowing someone who does the job you want so you “have some real life experience to base your decision on.”

You may not be good at what you are passionate about

Many an out-of-tune “American Idol” contestant has learned this message the hard way: “Just because you’re passionate about something doesn’t mean you won’t suck at it,” says Mike Rowe, the host of the Discovery Channel show “Dirty Jobs,” which covers some of the strangest jobs that people hold.

Indeed, there is often a gap between our passions and our skills, experts say. “You may love art and dream about being an artist, but if you’re not good at it, that passion won’t translate into a career for you,” says Palmer.

Or you may be good at certain parts of the job you’re passionate about, but not others — a fact that Southern California resident Jasmine Powers found out the hard way. Fed up with her administrative job, nine years ago Powers struck out on her own to pursue her passion of becoming a freelance events specialist.

But she soon realized that, while she was great at the events side of her business, she struggled with how to sell her services to clients. “I love working with other small businesses doing consulting and event marketing, but with a crowded marketplace of digital marketing experts and savvy founders, I struggled to prove my value and turn significant profits,” she says.

Palmer advises that those looking to pursue a passion career “do a reality check and be honest with yourself about your abilities before moving forward.”

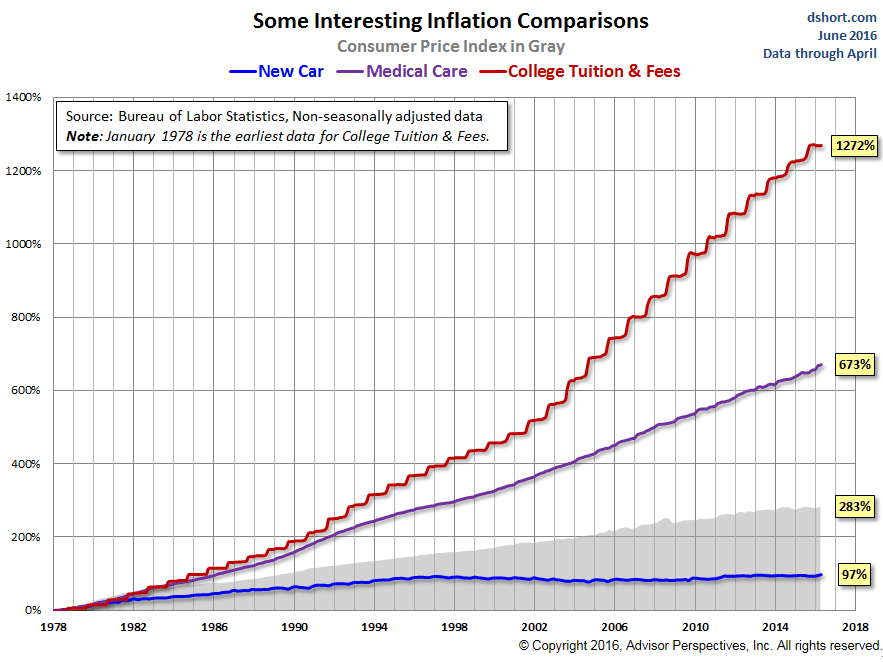

You may not be able to support yourself on your passion

Many people are passionate about career paths that simply won’t pay their bills, experts say. For example, while tens of thousands of Americans are passionate about crafting, it’s hard to make a living doing it. Indeed, there are few jobs — just over 50,000, about half of which are self-employed people — in the crafting and fine arts arena, and median pay isn’t great at just over $21 per hour, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. “You might enjoy making hats, but a little research will show you that milliners do not have a bright future in the U.S.,” says Palmer.

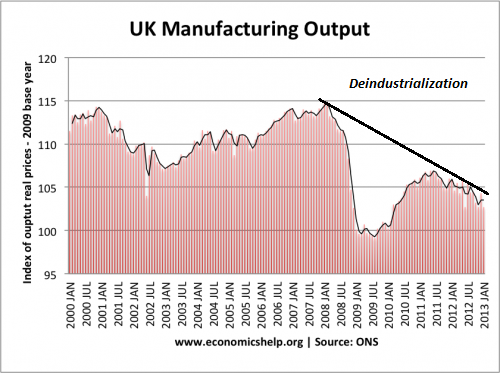

What’s more, “you may be passionate about a dying field,” says Palmer. And that means that while it may pay the bills now, there may not be a future in it for you.

So, unless you’re independently wealthy or have a pile of savings, you likely need to consider whether your passion can pay. Palmer stresses the importance of researching what the demand is for the field you want to enter (the Bureau of Labor Statistics has data on this). And Gurney says that some people may have to pursue their passion as a secondary career, while they do something else to pay the bills.

Of course, there are a many reasons to follow your passion for your career — among them personal fulfillment, happiness and peace of mind, experts say. But it’s important to remember that it may not work out, and that even if it does, it may not be as lucrative or as fulfilling as you’d hope. As business consultant Thom Fox puts it: “It’s a mixed bag.”

Shutterstock.com

Shutterstock.com