WASHINGTON

(AP) -- Four out of 5 U.S. adults struggle with joblessness,

near-poverty or reliance on welfare for at least parts of their lives, a

sign of deteriorating economic security and an elusive American dream.

Survey

data exclusive to The Associated Press points to an increasingly

globalized U.S. economy, the widening gap between rich and poor, and the

loss of good-paying manufacturing jobs as reasons for the trend.

The

findings come as President Barack Obama tries to renew his

administration's emphasis on the economy, saying in recent speeches that

his highest priority is to "rebuild ladders of opportunity" and reverse

income inequality.

As nonwhites approach a

numerical majority in the U.S., one question is how public programs to

lift the disadvantaged should be best focused - on the affirmative

action that historically has tried to eliminate the racial barriers seen

as the major impediment to economic equality, or simply on improving

socioeconomic status for all, regardless of race.

Hardship

is particularly growing among whites, based on several measures.

Pessimism among that racial group about their families' economic futures

has climbed to the highest point since at least 1987. In the most

recent AP-GfK poll, 63 percent of whites called the economy "poor."

"I

think it's going to get worse," said Irene Salyers, 52, of Buchanan

County, Va., a declining coal region in Appalachia. Married and divorced

three times, Salyers now helps run a fruit and vegetable stand with her

boyfriend but it doesn't generate much income. They live mostly off

government disability checks.

"If you do try

to go apply for a job, they're not hiring people, and they're not paying

that much to even go to work," she said. Children, she said, have

"nothing better to do than to get on drugs."

While

racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to live in poverty, race

disparities in the poverty rate have narrowed substantially since the

1970s, census data show. Economic insecurity among whites also is more

pervasive than is shown in the government's poverty data, engulfing more

than 76 percent of white adults by the time they turn 60, according to a

new economic gauge being published next year by the Oxford University

Press.

The gauge defines "economic insecurity"

as experiencing unemployment at some point in their working lives, or a

year or more of reliance on government aid such as food stamps or

income below 150 percent of the poverty line. Measured across all races,

the risk of economic insecurity rises to 79 percent.

Marriage

rates are in decline across all races, and the number of white

mother-headed households living in poverty has risen to the level of

black ones.

"It's time that America comes to

understand that many of the nation's biggest disparities, from education

and life expectancy to poverty, are increasingly due to economic class

position," said William Julius Wilson, a Harvard professor who

specializes in race and poverty. He noted that despite continuing

economic difficulties, minorities have more optimism about the future

after Obama's election, while struggling whites do not.

"There

is the real possibility that white alienation will increase if steps

are not taken to highlight and address inequality on a broad front,"

Wilson said.

---

Nationwide,

the count of America's poor remains stuck at a record number: 46.2

million, or 15 percent of the population, due in part to lingering high

unemployment following the recession. While poverty rates for blacks and

Hispanics are nearly three times higher, by absolute numbers the

predominant face of the poor is white.

More

than 19 million whites fall below the poverty line of $23,021 for a

family of four, accounting for more than 41 percent of the nation's

destitute, nearly double the number of poor blacks.

Sometimes

termed "the invisible poor" by demographers, lower-income whites

generally are dispersed in suburbs as well as small rural towns, where

more than 60 percent of the poor are white. Concentrated in Appalachia

in the East, they are numerous in the industrial Midwest and spread

across America's heartland, from Missouri, Arkansas and Oklahoma up

through the Great Plains.

Buchanan County, in

southwest Virginia, is among the nation's most destitute based on median

income, with poverty hovering at 24 percent. The county is mostly

white, as are 99 percent of its poor.

More

than 90 percent of Buchanan County's inhabitants are working-class

whites who lack a college degree. Higher education long has been seen

there as nonessential to land a job because well-paying mining and

related jobs were once in plentiful supply. These days many residents

get by on odd jobs and government checks.

Salyers'

daughter, Renee Adams, 28, who grew up in the region, has two children.

A jobless single mother, she relies on her live-in boyfriend's

disability checks to get by. Salyers says it was tough raising her own

children as it is for her daughter now, and doesn't even try to

speculate what awaits her grandchildren, ages 4 and 5.

Smoking

a cigarette in front of the produce stand, Adams later expresses a wish

that employers will look past her conviction a few years ago for

distributing prescription painkillers, so she can get a job and have

money to "buy the kids everything they need."

"It's pretty hard," she said. "Once the bills are paid, we might have $10 to our name."

---

Census

figures provide an official measure of poverty, but they're only a

temporary snapshot that doesn't capture the makeup of those who cycle in

and out of poverty at different points in their lives. They may be

suburbanites, for example, or the working poor or the laid off.

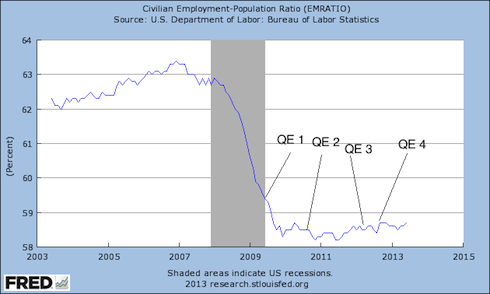

In

2011 that snapshot showed 12.6 percent of adults in their prime

working-age years of 25-60 lived in poverty. But measured in terms of a

person's lifetime risk, a much higher number - 4 in 10 adults - falls

into poverty for at least a year of their lives.

The

risks of poverty also have been increasing in recent decades,

particularly among people ages 35-55, coinciding with widening income

inequality. For instance, people ages 35-45 had a 17 percent risk of

encountering poverty during the 1969-1989 time period; that risk

increased to 23 percent during the 1989-2009 period. For those ages

45-55, the risk of poverty jumped from 11.8 percent to 17.7 percent.

Higher

recent rates of unemployment mean the lifetime risk of experiencing

economic insecurity now runs even higher: 79 percent, or 4 in 5 adults,

by the time they turn 60.

By race, nonwhites

still have a higher risk of being economically insecure, at 90 percent.

But compared with the official poverty rate, some of the biggest jumps

under the newer measure are among whites, with more than 76 percent

enduring periods of joblessness, life on welfare or near-poverty.

By

2030, based on the current trend of widening income inequality, close

to 85 percent of all working-age adults in the U.S. will experience

bouts of economic insecurity.

"Poverty is no

longer an issue of `them', it's an issue of `us'," says Mark Rank, a

professor at Washington University in St. Louis who calculated the

numbers. "Only when poverty is thought of as a mainstream event, rather

than a fringe experience that just affects blacks and Hispanics, can we

really begin to build broader support for programs that lift people in

need."

The numbers come from Rank's analysis

being published by the Oxford University Press. They are supplemented

with interviews and figures provided to the AP by Tom Hirschl, a

professor at Cornell University; John Iceland, a sociology professor at

Penn State University; the University of New Hampshire's Carsey

Institute; the Census Bureau; and the Population Reference Bureau.

Among the findings:

-For

the first time since 1975, the number of white single-mother households

living in poverty with children surpassed or equaled black ones in the

past decade, spurred by job losses and faster rates of out-of-wedlock

births among whites. White single-mother families in poverty stood at

nearly 1.5 million in 2011, comparable to the number for blacks.

Hispanic single-mother families in poverty trailed at 1.2 million.

-Since

2000, the poverty rate among working-class whites has grown faster than

among working-class nonwhites, rising 3 percentage points to 11 percent

as the recession took a bigger toll among lower-wage workers. Still,

poverty among working-class nonwhites remains higher, at 23 percent.

-The

share of children living in high-poverty neighborhoods - those with

poverty rates of 30 percent or more - has increased to 1 in 10, putting

them at higher risk of teenage pregnancy or dropping out of school.

Non-Hispanic whites accounted for 17 percent of the child population in

such neighborhoods, compared with 13 percent in 2000, even though the

overall proportion of white children in the U.S. has been declining.

The

share of black children in high-poverty neighborhoods dropped from 43

percent to 37 percent, while the share of Latino children went from 38

percent to 39 percent.

-Race disparities in

health and education have narrowed generally since the 1960s. While

residential segregation remains high, a typical black person now lives

in a nonmajority black neighborhood for the first time. Previous studies

have shown that wealth is a greater predictor of standardized test

scores than race; the test-score gap between rich and low-income

students is now nearly double the gap between blacks and whites.

---

Going

back to the 1980s, never have whites been so pessimistic about their

futures, according to the General Social Survey, a biannual survey

conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago. Just 45 percent say

their family will have a good chance of improving their economic

position based on the way things are in America.

The

divide is especially evident among those whites who self-identify as

working class. Forty-nine percent say they think their children will do

better than them, compared with 67 percent of nonwhites who consider

themselves working class, even though the economic plight of minorities

tends to be worse.

Although they are a

shrinking group, working-class whites - defined as those lacking a

college degree - remain the biggest demographic bloc of the working-age

population. In 2012, Election Day exit polls conducted for the AP and

the television networks showed working-class whites made up 36 percent

of the electorate, even with a notable drop in white voter turnout.

Last

November, Obama won the votes of just 36 percent of those noncollege

whites, the worst performance of any Democratic nominee among that group

since Republican Ronald Reagan's 1984 landslide victory over Walter

Mondale.

Some Democratic analysts have urged

renewed efforts to bring working-class whites into the political fold,

calling them a potential "decisive swing voter group" if minority and

youth turnout level off in future elections. "In 2016 GOP messaging will

be far more focused on expressing concern for `the middle class' and

`average Americans,'" Andrew Levison and Ruy Teixeira wrote recently in

The New Republic.

"They don't trust big

government, but it doesn't mean they want no government," says

Republican pollster Ed Goeas, who agrees that working-class whites will

remain an important electoral group. His research found that many of

them would support anti-poverty programs if focused broadly on job

training and infrastructure investment. This past week, Obama pledged

anew to help manufacturers bring jobs back to America and to create jobs

in the energy sectors of wind, solar and natural gas.

"They feel that politicians are giving attention to other people and not them," Goeas said.

---

AP

Director of Polling Jennifer Agiesta, News Survey Specialist Dennis

Junius and AP writer Debra McCown in Buchanan County, Va., contributed

to this report.