(

Steven Malanga)

The New Jersey legislature, looking to solve a budget crisis back in

1992, passed a bill that changed some of the accounting principles of

the state’s government employee pension system. The technical changes,

little understood at the time, made the system seem in better financial

shape than it actually was, allowing the legislature to reduce

contributions for pensions by $1.5 billion over the next two years.

Legislators seized those extra dollars and redirected them into other

spending.

Jersey officials could manipulate their pension system because local

governments have latitude in how they run their own retirement plans. So

what they did was not unique. Around the country, state and local

officials have increasingly discovered over the years that they can

exploit the complex and sometimes ill-defined accounting of government

pension systems, as well as loopholes in their own laws governing those

pensions.

Over time, elected officials came to promise workers politically

popular new benefits without setting aside the money to pay for them,

declared “holidays” from contributions into pension systems and changed

their own accounting systems midstream to make the systems seem better

funded — all just ways of passing obligations on to future taxpayers. In

the process, government pension systems became one of the chief

vehicles that state and local politicians used to massage their budgets.

Now we face the consequences. Our elected representatives played a

deceptive game of chicken with pension funds. And now the chickens have

come home to roost.

Years of gimmicks and politically motivated benefit increases for

government workers have left America’s states and municipalities with

pension funds that are short at least $1.5 trillion — and possibly as

much as $4 trillion if the investment returns of these funds don’t live

up to expectations in coming years. Just so the word “trillion” does not

pass by too quickly, let’s put it another way: That shortfall may be

$4,000,000,000,000.

Taxpayers are already paying the price. Since 2007, states and

localities have been forced to increase annual contributions into

pensions by $43 billion, or 65 percent, and in various places these

rising payments are crowding out other government services or driving

taxes higher or both. Retirement debt has even played a crucial role in

high-profile government bankruptcies — including in Detroit; Stockton,

California; and Central Falls, Rhode Island. Fixing the problem is

proving expensive, and it won’t happen quickly in places with the worst

debt.

At the root of the trouble are government pension systems, which

today differ vastly from the way they looked when many were created

about 100 years ago. Most states and localities initially designed

systems based on conservative accounting principles that were meant to

provide employees with a modest financial cushion for retirement —

pensions calculated to last a few years at best. The country’s largest

government employee pension, the California Public Employees’ Retirement

System, or Calpers, was formed in just such a way when it began

operating in 1932.

The system set the retirement age for employees at 65 years old, at a

time when the average worker 21 years of age could expect to live for

another 45 years, or until age 66. To reduce risks for the taxpayer,

California law limited the pension fund to invest in relatively safe

securities, such as U.S. Treasury bonds. Since these investments

generally produced modest returns, pensions themselves were modest. A

worker retiring after qualifying for a full pension could expect to

receive about 55 percent of his final salary in retirement.

But as government employees gained political influence, especially

through the emergence of public sector unions beginning in the late

1950s, they began lobbying for higher benefits. Politicians looking for a

way to satisfy those demands without busting their budgets fashioned

changes that made pension systems riskier to taxpayers, who cannot pass

the buck on to anyone else.

Hoping to generate higher returns, for instance, states and cities

began allowing retirement systems to invest in more speculative

financial products, such as stocks. Politicians also boosted benefits

without genuinely accounting for what that would cost over time.

Some people grew worried. A 1978 report to Congress on state and

local government retirement plans warned “there is an incomplete

assessment of true pension costs at all levels of government,” which

“impeaches the credibility” of many of the pension plans.” Adding that

“the potential for abuse is great,” the report called for federal

regulation of state and local pension plans. But officials in

Washington, fretting that legislation regulating state government

operations wouldn’t be constitutional, instead recommended changes to

accounting standards that the states were free to adopt — or ignore.

What seemed like an emerging problem receded into the background once

the stock market boom began in the 1980s. Assets in pension systems

grew rapidly as stocks went on a 20-year run, with just occasional short

downturns interrupting the good times. To elected officials and public

sector workers, the stock surge seemed to provide free money. Some local

governments responded by sharply increasing the benefits they promised.

They lowered retirement ages to 50 for public safety workers and to 55

or 60 for other government employees, even as Americans were living

longer. They also increased pension paychecks. In California, for

instance, legislation in 1999 allowed public safety workers to earn up

to 90 percent of their final salary as a pension upon full retirement.

States and cities added expensive perks, such as cost-of-living

increases. In Illinois, thanks to changes over the years that came to

guarantee retirees an annual boost in the value of their pension, a

worker retiring with a full pension at age 62 could double his pension

over the next 14 years. Governments began granting retirees another

costly perquisite — health insurance for life — even though the majority

of those governments set no money aside to pay for these promises.

The stock boom perversely encouraged politicians to take on ever more

risk. Many states and cities, for instance, stopped making meaningful

contributions from their budgets into pension funds and instead began

borrowing money and depositing it into their retirement systems, betting

that their investment managers could generate better returns in the

stock market than the cost of interest on the bonds. The move was the

equivalent of a worker taking out a home equity loan and placing the

money in his IRA to invest for retirement, something no responsible

investment adviser would counsel.

From the late 1980s through 2009, according to a study by the Boston

College Center for Retirement Research, 236 state and local governments

issued nearly 3,000 pension bonds totaling $53 billion. In 1998, for

instance, New Jersey floated $2.7 billion in debt for its underfunded

pension system, agreeing to pay investors back $10 billion over 30 years

for the borrowing. Illinois went much further, issuing a whopping $10

billion in bonds in 2003 alone. Financially troubled Detroit, short of

cash, floated $1.44 billion in pension bonds in 2005.

One perverse consequence of these offerings is that the borrowed

money made pension systems seem better funded than they actually were,

which provoked further benefit increases. From 1999 to 2003, New

Jersey’s legislature increased worker benefits 13 times at an additional

cost of $5 billion to the pension system. In Detroit, the pension

system handed out bonus checks to retirees after the 2005 borrowing,

even as the city’s finances deteriorated and Detroit spiraled toward

bankruptcy.

All of this new risk started to unravel pension systems when the

stock market stalled, first in 2000 with the end of the technology stock

bubble, and then again in late 2001, with the sharp decline in markets

after the Sept. 11 attacks, and then again in 2008, when the housing

bubble burst. Assets in pension systems plunged, and those with the

riskiest investment strategies suffered the most. California’s giant

Calpers fund had forged heavily into speculative real estate investment

starting in the late 1990s. When the mortgage bubble burst in 2008, the

fund’s real estate portfolio lost nearly half its value.

Some government retirement systems, facing severe shortfalls, began

demanding greater contributions from governments. San Jose, California,

for instance, saw its required pension contributions soar from $72

million annually in 2002 to $250 million by 2012. Short of cash and

anxious to keep costs from growing even more, the city began laying off

workers, eventually shrinking its workforce by 2,000.

Across the country in New York City, pension costs rose from $1.5

billion annually in 2002 to $8.5 billion by 2012. Those increases ate up

big chunks of money the city had stashed away during the stock market

boom. School districts, where compensation is a significant part of

total costs, also faced rapidly growing payments. The Philadelphia

school district spent about $35 million of its budget on pensions in

2005; last year pensions cost the Philly schools $155 million. In

response, the state legislature allowed Philadelphia to raise taxes by

tens of millions of dollars.

In some places, politicians unwilling to make tough decisions

initially refused to raise payments into pension systems or cut

benefits, hoping that some unanticipated stock market boom would solve

their funding problems. But such delays only made things worse. In 2010,

a state government report warned that California’s teacher pension fund

was on a “path to insolvency.” Not until last year, however, did the

state finally resolve to send more money into the system — at a great

cost to school districts around the state. Between now and 2020, their

payments for pensions will triple, from less than $1 billion in the

aggregate annually to more than $3.7 billion.

Similarly, after the stock market tanked in 2008 and the country

dipped into a deep recession, the Pennsylvania legislature allowed

school districts to reduce their contributions into the pension system

for teachers. But legislators also resisted cutting the cost of the

pension system by reducing benefits. Now the teachers’ pension system is

so badly funded that the state, under pressure from fiscal watchdogs,

has demanded sharply higher contributions from schools equivalent to 16

percent of the teachers’ salaries. That’s the highest contribution rate

in the history of the fund dating back to 1955. Years of similarly steep

pension contributions lie ahead.

Around the country, taxpayers watching these scenarios unfold began

demanding reforms and then electing politicians promising change. But in

many places, reformers woke up to a startling reality: Over the years,

legislators and state courts had granted unusually strong protections to

government worker pensions, far greater than the kinds of protections

that private workers enjoy. That has made cutting the cost of pensions

difficult, if not impossible, in some places with the deepest debts.

In 1974, Congress passed the Employee Retirement Income Security Act

to provide standards and protections for private sector pensions. That

law, and the way federal courts have interpreted it, protects the

pension wealth that a worker has already earned. But an employer has the

right to change the rate at which a worker earns pension benefits in

the future. And so, an employer who is setting aside the equivalent of

10 percent of a worker’s salary toward pensions could decide that next

year it will contribute only 5 percent. The worker has the right to

accept that, or find other employment.

But the ERISA law doesn’t apply to state and local pensions. As a

result, state legislators and courts have shaped pension law for

government employees, and in half of the states, reformers have found it

virtually impossible to make any changes to pensions for any current

workers, even for work they have yet to do. In Arizona, for instance, a

judge in 2012 overturned pension reforms that required state workers to

contribute more toward their pensions, ruling that those changes could

apply only to new workers.

In California, a court undid significant portions of reforms passed

by San Jose voters in a 2012 ballot initiative that sought to have

workers contribute more toward their retirements. The judge based her

decision on previous state court rulings that had said state legislation

creating government pensions is a contract with the worker that goes

into effect on the first day of the worker’s employment — and can’t be

altered for as long as he works for the government.

The problem that governments face in states like this, where

virtually any changes to pensions for current workers are banned, is

that the cost of paying for benefits that workers are earning is rising

even as municipalities struggle to pay off the debt that’s already

amassed. Consider the case of Sacramento. Its price tag for funding new

pension benefits increased by $9 million, or 37 percent, from 2006 to

2013. At the same time, Sacramento’s bill for paying off the debt

accumulated in its pension funds soared from $12 million in 2006 to

$23.4 million in 2013. The net increase from both of those factors

amounted to nearly $21 million, or 55 percent, in higher costs in just

six years.

These laws and rulings that make it difficult to reform pensions have

contributed to fiscal meltdowns in places such as Detroit and Stockton.

After Detroit came close to running out of money, Michigan Gov. Rick

Snyder hired an outside financial manager to study the city’s

predicament. That emergency manager, Kevyn Orr, said the city’s debts,

including $3.5 billion in unfunded pension obligations and another $5.7

billion in promises to pay healthcare for retirees, were simply too

great for the city to pay off, especially with Michigan’s strong

protections against any changes to pensions. Orr instead placed Detroit

into federal bankruptcy court in 2013, where it’s possible to reduce

such debt. Employees lost some of their pension and retiree healthcare

benefits as a result.

Similarly, officials in Stockton spent years enhancing benefits to

workers without understanding the debts they were accruing. The city

agreed back in the 1990s, for instance, to pay not only its own share of

contributions into the pension system, but those of staff, too. It also

guaranteed healthcare for life for retirees.

“Nobody gave a thought to how it was eventually going to be paid

for,” said Bob Deis, a financial manager the city hired in 2010 to start

clearing up its financial mess. Facing $400 million in pension debt and

$450 million in promises for future healthcare, the city declared

bankruptcy in 2012. Employees lost some of their perks, like healthcare

in retirement, but citizens suffered, too. Trying to save money, the

city cut essential services, including the police department, and crime

soared. “Welcome to the second most dangerous city in California,” said a

billboard placed in Stockton around the time of the bankruptcy.

Places that cannot reform pensions, or where legislators were slow to

act, are inevitably seeing tax increases to finance these steep

obligations. In Pennsylvania, 164 school districts applied in 2014 to

increase property taxes above the state’s 2.1 percent tax cap. Every one

of them listed pension costs as a reason for the higher increases. In

West Virginia, the state has given cities the right to impose their own

sales tax to pay for increased pension costs.

Several cities, including Charleston, have already gone ahead with

the new tax. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel tried to impose a $250 million

property tax increase last year to start wiping out pension debt in the

Windy City, where pensions are only 35 percent funded. When the City

Council balked, Chicago instead passed $62 million in other taxes,

including a levy on cell phone use, as a stopgap measure. But the city

faces a pension bill that is scheduled to rise by half a billion dollars

annually in 2016.

Not every place is facing such fiscal stress. Although the total debt

of state and city pensions is worryingly large, the burden is not

evenly distributed. Some states and municipalities remained true to

responsible accounting principles and didn’t increase benefits without

funding them. Others moved swiftly to fix problems as soon as they

emerged.

Utah, for instance, had a pension system that was nearly 100 percent

funded in 2007. When its debt rose after the stock market meltdown of

2008, the state quickly enacted reforms for new workers. It created a

defined contribution plan, in which workers accumulate money in

individual accounts, for new employees, and placed a limit on how much

the state would contribute to pensions.

Other states, such as Colorado and Rhode Island, have reduced or

eliminated annual cost-of-living adjustments. Although these increases,

sometimes averaging 3-5 percent annually, can seem small, over time

COLAs add significantly to the cost of a pension system, especially

since workers can live for 20 years or more after retiring. One 2010

study by two finance professors, Robert Novy-Marx of the University of

Rochester and Joshua Rauh of Stanford University, estimated that COLA

promises alone account for nearly half of all the state and local

pension debt.

But digging out of pension debt for other states will be far harder

because they’re so deep in the mire. A 2013 Moody’s report ranked the

states with the biggest pension debt relative to their state revenues as

Illinois, Connecticut, Kentucky and New Jersey. New Jersey passed

pension reform in 2011 that suspended COLAs, required higher

contributions by workers toward their pensions and raised retirement

ages. But the state, which a decade ago was contributing virtually

nothing out of its budget into pensions, still faces rising taxpayer

contributions to fix the system.

By 2018, Jersey will have to pay about $4 billion a year into

pensions, even after the reforms of 2011, so Gov. Chris Christie has

proposed new reforms, including closing the current pension system,

where workers earn a percentage of their final salary as a pension, and

shifting workers into a defined contribution plan similar to what most

private workers now enjoy, where they accumulate a pot of money in an

individual retirement account. Last week, the Supreme Court said

Christie could forego a $1.6 billion pension fund payment.

The varying levels of retirement woes among states and cities will

produce a landscape of winners and losers. In places with the deepest

debt, taxpayers face rising taxes and declining services, which is

hardly the sort of place that a family or a business wants to call home.

As Emanuel said back in 2012, without reform of its pension system, the

city faced a future where “you won’t recruit a business, you won’t

recruit a family to live here.”

The problem for America is that Chicago is not alone — far from it.

Steven Malanga is City Journal’s senior editor, a Manhattan

Institute senior fellow, and author of Shakedown: The Continuing

Conspiracy Against the American Taxpayer.

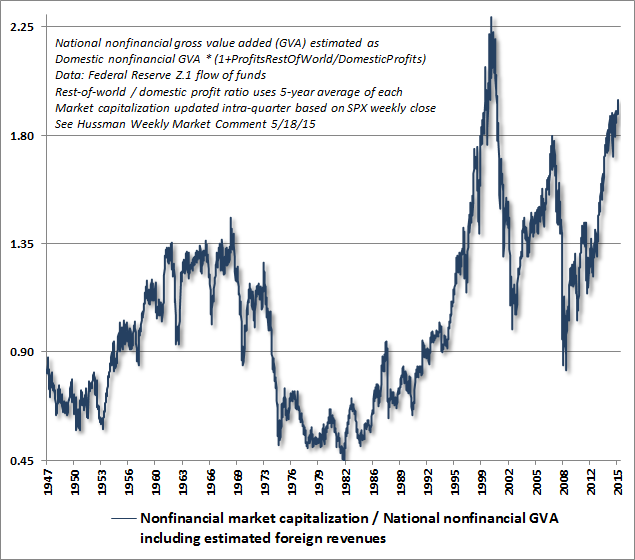

When you look back on this moment in history, remember

that spectacular extremes in reliable valuation measures already told

you how the story would end.

When you look back on this moment in history, remember

that spectacular extremes in reliable valuation measures already told

you how the story would end.