Wolf Richter

wolfstreet.com,

www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Benefiting hedge funds and banks that had front-run the fund.

Abenomics is facing elections on July 10 for the less powerful Upper House.

But Abenomics hasn’t fared very well. It engaged in the biggest

(relative to the economy) money-printing and bond buying extravaganza

the world has ever seen. The securities the Bank of Japan has bought,

now at ¥426 trillion ($4.15 trillion), amount to 85% of GDP. About $8

trillion in Japanese Government Bonds sport negative yields. Even the

30-year yield is just about zero. The JGB market, once the second

largest government bond market in the world, has frozen. The BOJ’s

primary dealers are in revolt. Some have already pulled out.

Savers are scared. Sales of safes to be installed at home have

soared. There have been no structural reforms to speak of. Japan Inc.

has benefited enormously, through various tax benefits and special

stimulus packages, including foreign aid that is channeled back to

Japanese companies. Government deficits are gigantic, providing

additional stimulus for Japan Inc. And yet, the economy is languishing.

So Abenomics is facing its

voters again. Few people on earth are as cynical about their elected

officials as Japanese voters. Any remaining illusions have been wrung

out of them years ago. In polls, voters have explained that they have

not benefited from Abenomics. Yet, Prime Minister’s Shinzo Abe’s

position remains strong, mainly because the opposition is so flimsy.

His conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has been in power

since its beginning in 1955, except for an 11-month stint in 1993/94,

and from 2009 to 2012. At the end of 2012, Abenomics was installed.

But there’s something that makes the Japanese nervous: how

politicians handle their pensions. Particularly older voters. They make

up a big part of the electorate. So the government decided not to rub

the effects of Abenomics in their faces and rile them unnecessarily just

before an election.

In April, it announced that it would delay the publication of the

annual results of the $1.36 trillion Government Pension Investment Fund

(GPIF), from the usual date in early July, to July 29. At the time, the

election date hadn’t been set yet, but it would have to be before July

25. So July 29 was a safe bet.

The election “has absolutely nothing to do with it,”

explained

GPIF spokesman Shinichirou Mori at the time. His excuse was that the

fund would be reviewing the results of the past 10 years and needs a

little extra time to put the report together.

But like so many things of Abenomics, it too flopped: after rumors of

huge losses had been swirling for months, the results were leaked.

“A person with direct knowledge of the matter,” and “speaking on condition of anonymity,” told

Reuters

that in fiscal 2015, which ended on March 31, the GPIF lost between ¥5

trillion and ¥5.5 trillion (between $49 billion and $53 billion).

This was the fund’s first annual loss since the Financial Crisis. All asset classes got hit, except – with hues of a

bitter irony – Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs).

In 2014, after Japanese stocks had soared for two years powered by

Abenomics money-printing and hedge-fund speculation, GPIF management

buckled under political pressure and announced that it would shift from

its conservative investment allocation focused on JGBs to one focused on

stocks and other riskier assets, in line with Abenomics.

The GPIF began selling its government bonds to the BOJ and started

buying stocks. It became the biggest buyer of equities in Japan, driving

up prices further. Other pension funds followed the model. In June

2015, the Nikkei hit its recent peak of 20,868 (

still 47% below

its all-time peak in 1989). But over the past 12 months, as the GPIF

curtailed its purchases since allocation goals were largely met, the

Nikkei has plunged 25%!

That plunge coincided largely with the fund’s fiscal year, which ended on March 31.

The fund showed ¥33.3 trillion in

cumulative investment income

from fiscal 2006 – when it was converted into an independent

administrative agency – through fiscal 2014. And in just one year, the

fund’s new focus on stocks annihilated 16.5% of the total gains

accumulated over nine years!

The source told Reuters that the preliminary results had been

presented to the fund’s investment committee last Thursday, June 29. So

the fund could have published the results as usual in early July. But

no.

At a regular news conference, Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary Koichi

Hagiuda denied any link between the delay of the publication of these

fiasco results and the Upper House election. The final results were

still being compiled, he said.

The funds mega-losses were picked up by the opposition, which

lambasted the government’s decision to plow the future of retirees into

risky assets.

“I’ve been warning about the problem of GPIF doing risk-high

investment,” Katsuya Okada, president of the Democratic Party, the

second largest party, told reporters, according to Reuters. With stocks

falling, “things are developing in the way I had feared.”

“We’re seeing a serious situation where pensions could be cut in the

future,” he said. “I’m also worried about GPIF’s huge presence in the

stock market. As a free-market economy, it’s undesirable to have a

situation where the government could influence stock moves,” he said,

having apparently forgotten for a moment that the BOJ is already buying

stocks to “influence” them.

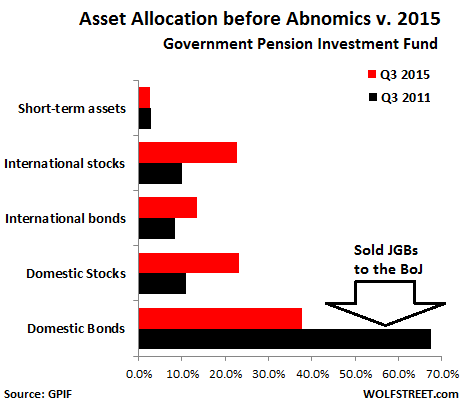

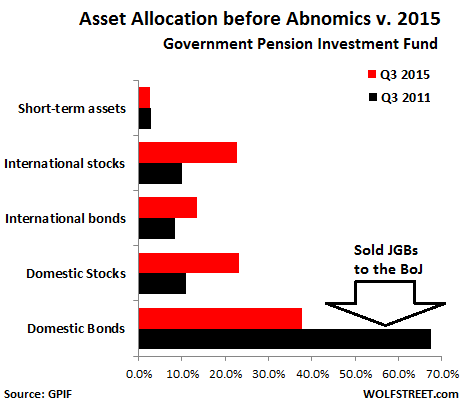

Here’s how the allocation has changed from Q3 2011, the last third

quarter before Abenomics came into being, and Q3 2015, the last quarter

available. Over the four years, the allocation of “domestic bonds”

declined from 67.4% to 37.8%, while the allocation of all other assets

jumped, with the allocation of international stocks and domestic stocks

more than doubling:

Alas, since April 2015, European and Japanese stocks have plunged,

while US stocks have gone nowhere. But the reviled JGBs that the BOJ is

buying with all its money-printing might rose.

The decision for switching into stocks in 2014 could not have been

better if the main objective had been to squander the pensions of

Japanese retirees for the benefit of hedge funds and banks that had been

able to front-run GPIF’s well-announced equity buying binge, only to

dump their darlings at peak prices into the lap of the eagerly buying

GPIF, where they’re now festering with losses.

This is what Abenomics has done to retirees, which Shinzo Abe is now

loathe to explain to them before the election. No wonder Japanese voters

are the most cynical in the word.

Now, with central banks flailing about wildly, mo one knows how to back out without blowing up the whole system. Read…

NIRP Absurdity Soars after Brexit, Hits $11.7 Trillion

One Step 4Ward

One Step 4Ward

FactSet

FactSet

FactSet

FactSet