Submitted by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

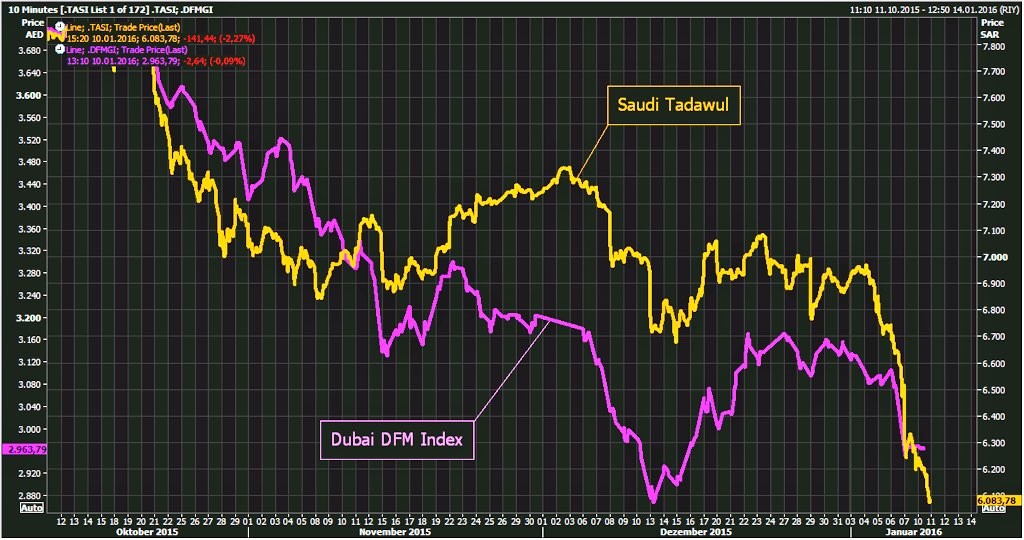

Advance signs of a global slump in economic activity emerged in 2015.

Furthermore, the dollar's strength, coupled with

widening credit spreads confirms a global tendency for

dollar-denominated debt to contract. These developments typically

precede an economic and financial crisis that could manifest itself in

2016, partially confirmed by the disappointing performance of equity

markets. If so, demand for physical gold can be expected to escalate

rapidly as a financial crisis unfolds.

Introduction

Gold has now been in a bear market since September

2011. Major central banks in the advanced economies have implemented

policies that have covertly suppressed the gold price, while they have

overtly inflated asset prices. This has led to valuation extremes in all

asset markets, including gold, that would never be seen in free markets

backed with sound money. We can be certain that today's unprecedented

build-up of price distortions will be corrected eventually by market

forces, probably in the coming months. The commencement of a crisis has

already been evidenced by the collapse in energy and

industrial-commodity prices, causing major problems for nations and

international companies with US dollar obligations and suddenly finding

they lack the revenue to service them. The scale of commodity-related

losses is not generally understood, but cannot be ignored for much

longer.

The rapid

expansion of central bank balance sheets since the Lehman crisis is the

ultimate phase of a process that can be traced back to at least the

1980s. Starting in London, US and European banks at that time took

control of securities markets. Since then, they have increasingly

directed bank credit at the expansion of those securities markets,

principally through the development of over-the-counter (OTC)

derivatives, but also by dominating bond and equity markets, and

regulated derivatives.

The expansion of bank credit aimed towards financial

activities has had the triple effect of inflating financial assets,

suppressing commodity prices below where they would otherwise be, and

enhancing international demand for the US dollar as the main pricing

currency. The result has been an unprecedented peace-time expansion of

global debt, while confidence in the reserve currency has been

maintained. However, there are indications that this period of expansion

is now at an end. According to the Bank for International Settlements'

statistical releases, the gross value of bank-held derivatives has been

contracting since 2013. Notional amounts of outstanding OTC contracts

peaked at end-2013 at $711 trillion, and by June 2015 had declined to

$553 trillion.

This is an important point, because an unseen bubble

at the heart of the financial system is deflating with unknown

consequences. When bubbles deflate, and here we are talking about one in

the hundreds of trillions, bad debts are usually exposed. Even though

much of the reduction in outstanding OTC derivatives is due to

consolidation of positions following the Frank Dodd Act, much of it is

not.

When free markets reassert themselves, and they

always do, the disruption promises to be substantial. We appear to be in

the early stages of this event.

Dollar and European dangers

As noted above, the rising value of the dollar

measured against commodities is a major problem. In the short-term the

dollar is extremely over-bought against record levels of commodity short

positions. Most notable is the dollar price of oil, with West Texas

Intermediate having fallen from $105 in June 2013 to $32 today. While

much of the fall can be attributed to lower demand from a slowing global

economy, some of it is undoubtedly due to the strength of the dollar

itself. Bad and potential bad debts, many commodity-related and

denominated in dollars, are a global issue, and the US banks are trying

to control their international loan exposure. Consequently,

international borrowers with dollar-denominated debt are being forced to

sell down local currencies to buy dollars in order to cover their

dollar obligations. The problem has been aggravated further by

speculators bidding up the dollar against these distressed buyers.

The dollar's overvaluation is also supported by the

belief that the US economy is healthy and performing relatively well.

With official unemployment down to 5%, demand for domestic credit, while

patchy, is basically sound and growing at a moderate pace. However,

nominal GDP growth is entirely due to monetary stimulus being not yet

offset by lagging price inflation, and is not the well-founded economic

recovery generally supposed. But for dollar bulls, the apparent strength

of the US economy is another reason to believe the dollar will remain

strong, given the prospect of a rising interest rate trend. There are

considerable dangers to this bullish view for the dollar, not least the

degree to which it is already discounted in current prices.

A second global problem is the financial and

economic condition of the Eurozone. 2015 saw the Greek crisis deferred,

but for 2016 we have the prospect of trouble from Spain and Portugal,

with government debt as a percentage of GDP estimated at 100% and 130%

respectively. In the Spanish general election in December an

anti-austerity combination of the left-wing Podemas and PSOE political

parties won 159 seats against the ruling party's 123. Negotiations are

now underway, but it looks like an anti-austerity coalition will form

the next government. Greece was difficult enough, but Spain is many

times greater in terms of its economic impact and the amount of

government debt involved. Also, Portugal, whose economy is about the

same size as that of Greece, had its general election in October, and

the ruling party lost its overall majority, suggesting that

anti-austerity pressures will increase in Lisbon as well. And Greece has

not gone away.

Greece in 2015 was the warm-up act for what's ahead

in the Eurozone. Meanwhile, €3 trillion of government bonds in Europe

now trade with negative yields, an unprecedented situation, which

illustrates how overvalued European government bonds in general have

become, particularly when taking into account the parlous condition of

some major governments' finances. The Eurozone banks are also

financially precarious, having an average Tier 1 capital ratio to

tangible assets of 5.1%, dropping to 4.1% when off-balance sheet items

are included. Furthermore, the netting off of credit default swaps

permitted under new Basel Committee rules has allowed the banks to

conceal their true loan risk. The combination of European banks gaming

the system, average core balance sheet leverage (including off-balance

sheet obligations) of 24:1, and their balance sheets laden with wildly

overvalued government bonds, has the makings of a crisis in search of a

trigger.

A European banking crisis could escalate very

rapidly if and when it starts, and would be an event beyond the direct

control of an alarmingly undercapitalised ECB. The initial effect might

be to drive the dollar higher in the foreign exchanges, particularly

against the euro, and instigate a further markdown of commodity prices,

as markets try to discount the economic implications of a systemic

problem in the Eurozone. If an event such as this occurs, it would be

impossible to limit it to a single geographical area. The major central

banks would be forced into a coordinated rescue programme, involving a

major expansion of all their balance sheets, on top of the post-Lehman

crisis expansion.

Once initial uncertainties are out of the way, the

prospect of escalating systemic risk should be very positive for gold,

which is the only certain hedge against these events. To determine the

potential for the gold price, its current value should be assessed by

looking at the long-run inflation of fiat dollars relative to the

increase of above-ground gold stocks, and adjusting the dollar price of

gold accordingly.

FMQ and gold

The fiat money quantity represents the total fiat

money that has been produced by the US banking system. It includes fiat

currency not in circulation, being mainly bank reserves sitting on the

Fed's balance sheet. The chart below shows the monthly accumulation of

US dollar FMQ since 1959.

Following the Lehman crisis, the dollar-price of gold fell initially

before recovering and gaining all-time highs in September 2011. With the

benefit of hindsight, we can surmise that the immediate effect of the

Lehman crisis was to trigger a flight into the dollar, before it became

evident that the Fed's actions aimed at stabilising the financial sector

were succeeding at the expense of monetary inflation. This also

provides an explanation as to why, in order to maintain confidence in

the dollar, the gold price had to be subsequently suppressed. Judging by

all the circumstantial evidence following the Cyprus crisis, the most

notable suppression exercise was in April 2013, and close study of

market actions and volumes reveals that other less dramatic price

suppressions have from time to time also taken place.

Given this experience, it would be wrong to rule out

another attempt by the western central banks to suppress the price of

gold in the event of a crisis. However, it is becoming clear that they

can only suppress the price through the paper markets, given the

relative scarcity of physical bullion in western central bank vaults,

and the reluctance of individual central banks to compromise their

bullion holdings any further. These short-term uncertainties cannot be

quantified, but we can have a clear idea as to gold's current true

value, expressed in US dollars. This is the subject of our next chart.

The chart shows the price of gold deflated by both

the increase in FMQ over the years and by the expansion of above-ground

gold stocks, since the price was fixed at $35 in 1934 by President

Roosevelt. Adjusted by these two factors, gold at end-December 2015 was

priced at the equivalent of $3.25 in 1934 dollars, less than 10% of the

1934 price. The only occasion the adjusted price has been lower was in

1971, just months before the Nixon shock, when the Bretton Woods system

finally collapsed. The adjusted price stood at $3.13 in March that year.

The next chart shows the same price adjustments

applied to the gold price, this time from August 2008, when the Lehman

crisis broke and the nominal gold price was $918.

The adjusted price, reflecting the expansion of both

the FMQ and above-ground gold stocks, now stands at $402, a decline of

56% in real terms since Lehman.

On value considerations, we can therefore conclude the following:

•

Gold is cheaper than it has ever been against the world's reserve

currency, with the single exception of the time when it was so

under-priced that the US Government was forced to scrap its peg at $35

and abandon the Bretton Woods Agreement.

• Compared with the

situation at the time of the Lehman crisis, gold is significantly

cheaper today, which is wholly at odds with the continuing systemic risk

to fiat currencies from undercapitalised banks, unprepared for the

prospect of markets normalising.

Many contemporary financial analysts would argue

that gold is not relevant to these issues, because gold is no longer

money. This line of reasoning ignores the fact that ordinary people in

the west do not get this message and are accumulating gold coins and

small bullion bars at increasing rates. And more

importantly, economic power is shifting from countries where this

Keynesian view is prevalent to countries where it is not. The next section looks at the geostrategic implications of the shift in the ownership and pricing of gold from west to east.

China, India and the rest of Asia

China and India, together with all the other

countries in mainland Asia, have been draining the west's vaults of

above-ground gold stocks for far longer than most people in western

capital markets realise. China first delegated the management of gold

policy to the Peoples Bank by regulations adopted in 1983, in a move

that followed the post-Mao reforms of 1979/82. The intention behind

these regulations was for the state to acquire substantial amounts of

gold, to develop gold mining, and to control all processing and refining

activities. At that time the west was doing its best to suppress gold

in order to enhance the credibility of paper currencies, by releasing

large quantities of vaulted bullion through leasing and outright sales.

This is why the timing is important: it was an opportunity for China,

with its one-billion plus population in the throes of rapid economic

reform, to diversify growing foreign currency surpluses, in the same way

as the Arab nations did earlier and contemporaneously between 1973-1990

following the oil price boom.

When China set up the Shanghai Gold Exchange in 2002

and encouraged its private sector to accumulate gold, the state had

obviously acquired enough bullion for its own strategic purposes. We

cannot know how much the state has actually accumulated, or indeed to

what extent the gold she has mined has been taken into state ownership

since, but the amount is likely to be very substantial. We do know that

gross deliveries into public hands since 2002, satisfied mainly by

imports from western vaults, exceed 11,000 tonnes to date. It is

therefore quite possible that China and its citizens now have more gold

than all the other central banks put together, given that some official

gold is currently leased by western central banks and some has been

secretly sold to suppress the price.

The monthly statements about China's gold reserve

additions are therefore meaningless. However, Russia is now accumulating

official reserves as well, and the Indian state is trying to acquire

her citizen's gold by stealth, having been frozen out of the market

through lack of supply. The bulk of Asia is, or will be, bound together

through the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, an economic partnership

dominated by China and Russia, encompassing more than half the world's

population, and which accepts physical gold as the ultimate form of

money. And what clearly emerged in 2015 is that the dominant trade

currency in this bloc will unquestionably be the Chinese yuan, the

currency of the country that has now cornered the world's physical gold

market.

The future for the world's money is rapidly developing, as will become increasingly apparent in 2016. The

era of dollar supremacy is coming to an end, no doubt hastened by the

Fed's ultimately destructive monetary policies. The threat to the

dollar's primacy is also a threat to the other great paper currencies:

the euro, the yen and sterling. Whether or not these fail before, with

or after the dollar, is only a matter for timing. China must have

foreseen this possible outcome, otherwise she would not have embarked on

a policy of accumulating gold as long ago as 1983, invested substantial

resources into gold mining and refining, actively encouraged her

citizens to own it, and is today promoting use of her currency for

global trade and the pricing of gold.

Western market observers seem to be unaware of how

advanced China's currency policy is today. Instead, they expect a

full-blown credit crisis, the result of the credit expansion of recent

years being undermined by a rapidly slowing economy. Furthermore, they

argue that Chinese labour costs have increased and require a much lower

yuan exchange rate to become competitive again. Based on western-style

macroeconomic analysis, they naturally conclude that China will require a

substantial currency devaluation to contain these problems.

While it is a mistake to gloss over the considerable

economic difficulties, this analysis is flawed on two counts. Firstly,

the state owns the banks, so a credit crisis stops with the debtors. And

secondly, under the thirteenth five-year plan, China is embarking on a

redirection of economic resources from being the cheap manufacturer for

the rest of the world to serving its growing middle class and developing

trans-Asian infrastructure. China's unemployment rate is estimated to

be about 5%, so workers employed on current production lines will need

to be redeployed, if the state's economic strategy is to progress. A

substantial devaluation is therefore counterproductive, though the

central bank does move the yuan's peg against the dollar from time to

time.

The purpose behind China's accumulation

of gold can only be to eventually make the yuan a reliable store of

value. China will need to see a higher gold price in yuan, probably at a

time dictated by external events, which she will patiently await. This

is why, having developed the Shanghai Gold Exchange into the world's

most important physical gold market, China plans to price gold in yuan,

with the objective that the yuan-gold peg will eventually supersede

yuan-dollar peg.

We will surely end 2016 with a wider appreciation that the dollar is

no longer king, and that the future for money lies in Asia, the yuan,

and gold.

Conclusion

In the near-term, paper gold is extremely oversold,

reflecting the expression of western establishment sentiment in the

paper markets. Futures and forward markets are short of paper gold to an

extraordinary degree. Whether or not this leaves open the possibility

of further falls in the dollar price of gold in the next few months is a

moot point. More importantly, on longer-term considerations, gold has

not been this undervalued since the events leading to the collapse of

the Bretton Woods agreement. If current events lead to a

systemic crisis in western capital markets in 2016, which given the

global slump in economic activity looks increasingly likely, a further

expansion of central bank balance sheets on top of the post-Lehman

expansion seems certain. If this happens, it is unlikely the purchasing

power of the dollar and the other major currencies will remain at

current levels. And if the dollar loses purchasing-power, price

inflation will rise along with nominal interest rates, and a wider debt

liquidation in western capital markets becomes a real possibility.

China and her SCO partners have taken

steps to be protected from this outcome and have cornered the gold

market. A wise person should take note and think seriously about the

implications.

Enjoy 2016.

By John Vibes

By John Vibes