Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

There’s simply no respite.

Money is leaving China in myriad ways, chasing after overseas assets in near-panic mode. So Anbang Insurance Group, after having already acquired the Waldorf Astoria in Manhattan a year ago for a record $1.95 billion from Hilton Worldwide Holdings, at the time majority-owned by Blackstone, and after having acquired office buildings in New York and Canada, has struck out again.

It agreed to acquire Strategic Hotels & Resorts from Blackstone for a $6.5 billion. The trick? According to Bloomberg’s “people with knowledge of the matter,” Anbang paid $450 million more than Blackstone had paid for it three months ago!

Other Chinese companies have pursued targets in the US, Canada, Europe, and elsewhere with similar disregard for price, after seven years of central-bank driven asset price inflation [read…Desperate “Dumb Money” from China Arrives in the US].

As exports of money from China is flourishing at a stunning pace, exports of goods are deteriorating at an equally stunning pace. February’s 25% plunge in exports was the 11th month of year-over-year declines in 12 months, as global demand for Chinese goods is waning.

And ocean freight rates – the amount it costs to ship containers from China to ports around the world – have plunged to historic lows.

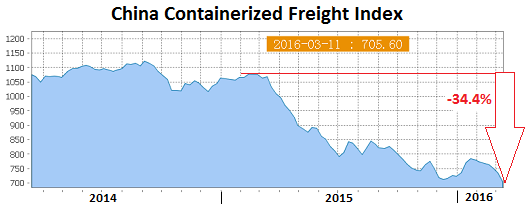

The China Containerized Freight Index (CCFI), published weekly, tracks contractual and spot-market rates for shipping containers from major ports in China to 14 regions around the world. Unlike most Chinese government data, this index reflects the unvarnished reality of the shipping industry in a languishing global economy. For the latest reporting week, the index dropped 4.1% to 705.6, its lowest level ever.

It has plunged 34.4% from the already low levels in February last year and nearly 30% since its inception in 1998 when it was set at 1,000. This is what the ongoing collapse in shipping rates looks like:

The rates dropped for 12 of the 14 routes in the index. They rose in only one, to the Persian Gulf/Red Sea, perhaps in response to the lifting of the sanctions against Iran, and remained flat to Japan. Rates on all other routes dropped, including to Europe (-7.9%), the US West Coast (-3.5%), the US East Coast (-1.0%), or the worst drop, to the Mediterranean (-13.4%).

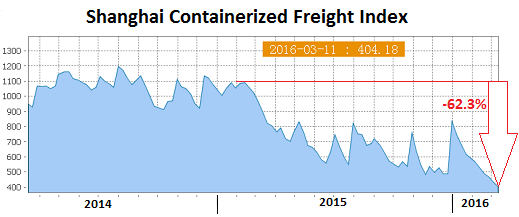

The Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (SCFI), which is much more volatile than the CCFI, tracks only spot-market rates (not contractual rates) of shipping containers from Shanghai to 15 destinations around the world. It had surged at the end of last year from record lows, as carriers had hoped that rate increases might stick this time and that the worst was over. But rates plunged again in the weeks since, including 6.8% during the last reporting week to 404.2, a new all-time low. The index is now down 62.3% from a year ago:

Rates were flat for three routes, but dropped for the other 12 routes, including to Europe, where rates plunged nearly 10% to a ludicrously low $211 per TEU (twenty-foot equivalent container unit). Rates to the US West Coast fell 8.4% to $810 per FEU (forty-foot equivalent container unit). Rates to the East Coast fell 5.2% to $1,710 per FEU. Rates to South America plunged 25.4%.

This crash in shipping rates is a result of two by now typical forces: rampant and still growing overcapacity and lackluster demand.

“Typical” because lackluster demand has been the hallmark of the global economy recently, and the problems of overcapacity have also been occurring in other sectors, including oil & gas and the commodities complex. Overcapacity from coal-mining to steel-making, much of it in state-controlled enterprises, has been dogging China for years and will continue to pose mega-problems well into the future. Overcapacity kills prices, then jobs, and then companies.

The ocean freight industry went on a multi-year binge buying the largest container ships the world has ever seen and smaller ones too. It was led by executives who believed in the central-bank dogma that radical monetary policy will actually stimulate the real economy, and they were trying to prepare for it. And it was made possible by central-bank-blinded yield-chasing investors and giddy bankers. As a result, after years of ballooning capacity, carriers added another 8% in 2015, even while demand for transporting containers across the oceans languished near the flat line, the worst performance since 2009.

“Massive Deterioration,” the CEO of Maersk, a bellwether for global trade, called the phenomenon. Read… “Worse than 2008”: World’s Largest Container Carrier on the Slowdown in Global Trade