Ludwig von Mises Institute – by Andrei Znamenski

Ludwig von Mises Institute – by Andrei Znamenski

Imagine a country that has a corrupt authoritarian government. In

that country no one knows about checks and balances or an independent

court system. Private property is not recognized in that country either.

Neither can one buy or sell land. And businesses are reluctant to bring

investments into this country.

Those who have jobs usually work for the public sector. Those who don’t

have jobs subsist on entitlements that provide basic food. At the same

time, this country sports a free health care system and free access to

education. Can you guess what country it is? It could be the former

Soviet Union, Cuba, or any other socialist country of the past.

Yet, I want to assure you that such a country exists right here in

the United States. And its name is Indian Country. Indian Country is a

generic metaphor that writers and scholars use to refer to the

archipelago of 310 Native American reservations, which occupy 2 percent

of the U.S. soil. Scattered all over the United States, these sheltered

land enclaves are held in trust by the federal government. So legally,

many of these land enclaves are a federal property. So there you cannot

freely buy and sell land or use it as collateral. On top of this, since

the Indian tribes are wards of the federal government, one cannot sue

them for

breach of contract. Indian reservations are communally used by Indian groups and subsidized by the BIA (the Bureau of Indian Affairs,

Department of the Interior)

with a current annual budget of about $3 billion dollars. Besides being

a major financial resource that sustains the reservation system, BIA’s

goal is also to safeguard indigenous communities, or, in other words, to

make sure that they would never fail when dealing with the “outside”

society. People in the government and many Native American leaders

naÏvely believe that it is good for the well-being of the Indians to be

segregated and sheltered from the rest of American society.

This peculiar trust status of Indian Country, where private property rights are insecure, scares away businesses and investors.

[1] They

consider these forbidden grounds high risk areas. So, in Indian

Country, we have an extreme case of what Robert Higgs famously labeled

“regime uncertainty” that retards economic development.

[2] In fact, this “regime uncertainty” borders on socialism.

James Watt,

Secretary of the Interior in the first Reagan administration, was the

first to publicly state this. In 1983, he said (and then dearly paid for

this), “If you want an example of the failure of socialism, don’t go to

Russia, come to America and go to the Indian reservations.”

[3]

In the 1990s, I had a chance to travel through several reservations.

Each time when I crossed their borders I was stunned by the contrast

between the human landscapes outside and those within Indian

reservations. As soon as I found myself within a reservation, I

frequently had

a taste of a world that, in appearance, reminded me of the countryside in Russia, my former

homeland:

the same bumpy and poorly maintained roads, worn-out shacks, rotting

fences, furniture, and car carcasses, the same grim suspicious looks

directed at an intruder, and frequently intoxicated individuals hanging

around. So I guess my assessment of the reservation system will be a

biased view from a former Soviet citizen who feels that he enters his

past when crossing into Native America.

I am going to make a brief excursion into the intellectual sources of

this “socialist archipelago.” Since the 1960s, the whole theme of

Native America had been hijacked by Marxist scholarship and by so-called

identity studies, which shaped a mainstream perception that you should

treat Native Americans not as individuals but as a collection of

cultural groups, eternal victims of capitalist oppression. I want to

challenge this view and address this topic from a standpoint of

methodological individualism. In my view, the enduring poverty on

reservations is an effect of the “heavy blanket” of collectivism and

state paternalism. Endorsed by the federal government in the 1930s,

collectivism and state paternalism were eventually internalized by both

local Native American elites and by federal bureaucrats who administer

the Indians. The historical outcome of this situation was the emergence

of “culture of poverty” that looks down on individual enterprise and

private property. Moreover, such an attitude is frequently glorified as

some ancient Indian wisdom — a life-style that is morally superior to

the so-called Euro-American tradition.

Before we proceed,

I will give you some statistics. Native Americans receive more federal

subsides than anybody else in the United States. This includes

subsidized housing, health, education, and direct food aid. Yet, despite

the uninterrupted flow of federal funds, they are the poorest group in

the country. The poverty level on many reservations ranges between 38

and 63 percent (up to 82 percent on some reservations),[4] and half of all the jobs are usually in the public sector.[5] This

is before the crisis of 2008! You don’t have to have a Ph.D. in

economics to figure out that one of the major sources of this situation

is a systemic failure of the federal Indian policies.

These policies were set in motion during the

New Deal by John

Collier, a Columbia-educated social worker, community organizer, and utopian dreamer who was in charge of

the Native

American administration during FDR’s entire administration. English

Fabian socialism, the anarchism of Peter Kropotkin, communal village

reforms conducted by the Mexican socialist government, and the romantic

vision of Indian cultures were the chief sources of his intellectual

inspiration. Collier

dreamed about

building up what he called Red Atlantis, an idyllic Native American

commonwealth that would bring together modernization and tribal

collectivism. He expected that this experiment in collective living

would not only benefit the Native Americans but would also become a

social laboratory for the rest of the world. The backbone of his

experiment was setting up so-called tribal governments on reservations,

which received the status of public corporations. Collier envisioned

them as Indian autonomies that would distribute funds, sponsor public

works, and set up cooperatives. In reality, financed by the BIA, these

local governments began to act as local extensions of its bureaucracy.

It is interesting that these so-called native autonomies received

peculiar jack-of-all-trades functions: legislative, executive, judicial

and economic — a practice that is totally unfamiliar in America. For

example, in the rest of the United States, municipalities and counties

do not own restaurants, resorts, motels, casinos, and factories. In

Indian Country, by contrast, it became standard practice since the New Deal.

By their status, these tribal governments are more interested in

distributing jobs and funds than in making a profit. As a result, many

enterprises set up on reservations have been subsidized by the

government for decades. Under normal circumstances, these ventures would

have gone bankrupt. This system that was set up in the 1930s represents

a financial “black hole” that sucks in and wastes tremendous resources

in the name of Native American sovereignty. This situation resembles the

negative effect of foreign aid on Third-World regimes that similarly

use the tribalism and national sovereignty excuse as a license to

practice corruption, nepotism, and authoritarian rule.

My major argument is that Collier’s utopian project (restoration of

tribal collectivism) was not a strange out-of-touch-with-reality scheme

but rather a natural offshoot of the social engineering mindset of New

Dealers. Moreover, the Indian New Deal was a manifestation of standard

policy solutions popular among policy makers in the 1930s, both in

Europe and North America. These solutions were driven by three key

concepts: state, science, and collectivism. Recent insightful research

done by German-American historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch into the

economics and cultures of three “new deals” (National Socialist Germany,

Mussolini’s Italy, and FDR’s United States) shows that in the interwar

period, governments in these three countries (and in other countries,

too) pursued extensive state-sponsored modernization. But,

simultaneously, to better mobilize their populations and ease the

pressure of modernization on the people, they cultivated a sense of

community, the organic unity with land and folk cultures.

[6]

For example, in 1930s Germany, along with the grand autobahn building

project and genetic experimentation, there existed a strong

back-to-land movement and attempts to revive Nordic paganism. In the

United States, in addition to the National Recovery Administration,

Tennessee Valley Authority and similar giant projects, there flourished

the community-binding Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Federal Art

Project that produced “heroic” community murals as well as thousands of

craft items for civic, state, and federal organizations. Furthermore,

as “one of the noblest and most absurd undertakings ever attempted by a

state” (W. H. Auden), Federal Writers’ Project (also part of WPA)

employed thousands of intellectuals who were directed to collect

regional folklore and ethnographies, and promote the heritage of local

communities. Last but not least, there were projects like the Arthurdale

settlement (West Virginia) — a federally sponsored scheme to place

unemployed industrial workers on land and mold them into new wholesome

American citizens.

[7] Even

Stalin’s Soviet Union, which was going wild with its aggressive

modernization and industrialization, somewhat muted the cosmopolitan

message of Communism and became more “organic” in the 1930s, trying to

root itself in Russian history, mythology, and folklore — pursuits that

became known as National Bolshevism.

[8]

Another common sentiment shared by social engineers from California

to the Ural Mountains was an unconditional faith in science. We can call

it science worship. At that time, policy makers assumed that by using

science and expert-scholars government could plan and engineer a

perfectly ordered crisis-proof society. F. A. Hayek was the first to

draw attention to this aspect of modernity in his seminal book

The Counter-Revolution of Science (1955).

[9]

The Indian New Deal fits perfectly into those policy trends. In fact,

as early as 1928, federal bureaucrats began suggesting that the Indians

be organized as public corporations — a fancy innovation that they

copied from Europe. Collier, a middle-level New Deal bureaucrat,

personified sentiments of modernism I mentioned above. On one hand, he

praised Indian tribalism that would help not only the Native Americans

but would also help anchor Americans in land and nourish a sense of

community among them. Yet, on the other hand, like a mantra, Collier

repeated that only a scientific approach would resolve the problems

communities faced in the modern world. A recurrent message throughout

his essays and articles is a demand that Indian communities be used as

laboratories for sociological experimentation. In one of his speeches —

which by the way is labeled “United States Administration as a

Laboratory of Ethnic Relations” — Collier gave himself an unrestricted

political license to experiment with Indian Country. In this speech, he

stressed that if a government tried to impose something on an ethic

group it would be harmful. Yet, if government intervention was backed up

by science and supplemented by generous financial injections to local

communities, then the interference would be very benign.

[10]

Where did Collier get his “scientific” ideas about segregating Native

Americans into cultural groups? The answer is simple: from contemporary

anthropological scholarship. At that time, American anthropologists

were very much preoccupied with traditional culture. They were on a

mission to retrieve ethnographically authentic Indian customs and

artifacts. Driven by this romantic notion, anthropologists downplayed

the heavy influence of Euro-Americans and African-Americans on

indigenous communities. As a result, they totally ignored such segments

of Indian population as cowboys, iron, cannery and agricultural workers,

and individual farmers. They considered them non-Indian and

non-traditional. So, before Collier emerged on the scene in 1933,

American anthropology had already invented its own Red Atlantis by

classifying the Indians into tribes and relegating them into particular

cultural areas.

Pressured by the federal government and lured by an offer of easy

credit, a majority of Indians approved of Collier’s plan to restore

“tribes” and organized themselves into public corporations. Still, a

large minority — more than 30 percent of the Indians — rejected the

Indian New Deal. Many of them informed Collier that, in fact, although

they were Indians, they had nothing against private property and did not

want be segregated from the rest of Americans into tribes under federal

supervision. They stressed that they could not stomach his communism

and socialism, and wanted instead to be treated as individuals. Collier

was very much surprised and angered by these dissidents, who organized

themselves and founded the American Indian Federation (AIF) to oppose

him. In a bizarre motion, he dismissed them as fake Indians. To him, the

true Indian was expected to be a spiritually-charged die-hard

collectivist. Historian Graham Taylor, who explored in detail Collier’s

attempts to railroad tribalism in Indian Country, stressed, “His basic

orientation was toward groups and communities, not individuals, as

building blocks of society.”

[11] Later,

Collier even resorted to nasty tricks labeling his Indian opponents as

Nazi collaborators, and had one of them investigated by the FBI.

Eventually, government squashed AIF as part of a larger FDR effort to

use the FBI to phase out the “right-wing fifth column” elements in the

United States.

[12] D.

H. Lawrence, the famous British novelist, who rubbed shoulders with

Collier as early as 1920, had a chance to personally observe his

aggressive zeal on behalf of Indian culture. This British writer

prophetically noted that Collier would destroy the Indians by setting

“the claws of his own white egoistic benevolent volition into them.”

[13]

To those dissident Native Americans who repeatedly challenged him

about going tribal, Collier explained that their individualism was

obsolete. In his view, state-sponsored tribalism was modern and

progressive. In his address given before the Haskell Institute, Collier

instructed students to cast aside “shallow and unsophisticated

individualism.” He warned the Indian youngsters that this useless trait

of dominant culture would not be “the views of the modern white world in

the years to come.” Instead, he called on the new Indian generation to

come help “the tribe, the nation, and the race.” He invited them to step

into a radiant future that included such “necessities of modern life”

as municipal rule, public ownership, cooperatives, and corporations.

[14]

The system set up by Collier is still in place and functioning. What

are its future prospects? As I mentioned, the Indian “socialist

archipelago” is relatively modest in its size. It occupies only 2

percent of U.S. soil and shelters only 22 percent of 5 million Indians

now living in the United States. Unlike bailing out such bankrupt states

as California, New York, and Illinois, socializing subsidies to Indian

Country is not too painful for a huge American budget. So, potentially,

this “socialist archipelago” can exist forever as long as American

taxpayers are ready to put up with its peculiar status, and unless, of

course, American welfare capitalism goes down under the burden of its

numerous entitlement obligations. So far, protected by the shield of

trust status and guaranteed financial injections, Indian Country is in

pretty “good shape,” unlike, for example, some current Third-World

autocracies that are not always sure if Western aid will continue to

flow. All in all, like the Social Security scheme, farmers’ subsidies,

and many other “wonderful” products of the New Deal alchemical lab, Red

Atlantis is still with us alive and well.

Notes

[1] Fergus Bordewich,

Killing the White man’s Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century (New York: Doubleday, 1997),p. 126; John Koppisch, “Why Are Indian Reservations So Poor? A Look At The Bottom 1%,”

Forbes, December 13 (2011), available at

http://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoppisch/2011/12/13/why-are-indian-reservations-so-poor-a-look-at-the-bottom-1/

[2] Robert Higgs, “Regime Uncertainty: Why the Great Depression Lasted So Long and Why Prosperity Resumed after the War,”

The Independent Review 1, no. 4 (1997): 561-590.

[3] Watt Sees Reservations As Failure of Socialism,”

The New York Times, January 19, 1983, http://www.nytimes.com/1983/01/19/us/watt-sees-reservations-as-failure-of-socialism.html

[4] “Native American Aid, Living Conditions,” available at http://www.nrcprograms.org/site/PageServer?pagename=naa_livingconditions

[5] Rachel L. Mathers, “The Failure of State-Led Economic Development on American Indian Reservations,”

The Independent Review 17, no. 1 (2012): 176.

[6] Wolfgang Schivelbusch,

Three New Deals: Reflections on Roosevelt’s America, Mussolini’s Italy, and Hitler’s Germany, 1933-1939 (New York: Picador, 2007).

[7] For more about the Arthurdale project, see C.J. Maloney,

Back to the Land: Arthurdale, FDR’s New Deal, and the Costs of Economic Planning (New York: Wiley, 2011).

[8] David Brandenberger,

National Bolshevism: Stalinist Mass Culture and the Formation of Modern Russian National Identity, 1931-1956 (Cambridge, MA and London: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[9] F. A. Hayek,

The Counter-Revolution of Science (New York: Free Press, 1955).

[10] John Collier, “United States Administration as a Laboratory of Ethnic Relations,”

Social Research 12, no. 3 (1945): 301.

[11] Graham Taylor

, The New Deal and American Indian Tribalism: The Administration of the Indian Reorganization Act, 1934-45 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1980), p. 23.

[12] Marci

Jean Gracey, Attacking the Indian New Deal: The American Indian

Federation and the Quest to Protect Assimilation (Masters’ Thesis,

Oklahoma State University, 2003), p. 47.

[13] Joel Pfister,

Individuality Incorporated: Indians and the Multicultural Modern (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2004), p. 182.

[14] Kenneth Philp,

John Collier’s Crusade for Indian Reform, 1920-54 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1977), p. 161.

As

for Najib, 39 percent of voters said he was qualified to be the prime

minister, while 31 percent disagreed. Another 30 percent were unsure.

As

for Najib, 39 percent of voters said he was qualified to be the prime

minister, while 31 percent disagreed. Another 30 percent were unsure. Thirty

nine percent of the respondents said they were convinced that the sex

video was a piece of "Umno propaganda" aimed at making personal attacks,

while 39 percent said they were unsure.

Thirty

nine percent of the respondents said they were convinced that the sex

video was a piece of "Umno propaganda" aimed at making personal attacks,

while 39 percent said they were unsure. As

for Najib, 39 percent of voters said he was qualified to be the prime

minister, while 31 percent disagreed. Another 30 percent were unsure.

As

for Najib, 39 percent of voters said he was qualified to be the prime

minister, while 31 percent disagreed. Another 30 percent were unsure. Thirty

nine percent of the respondents said they were convinced that the sex

video was a piece of "Umno propaganda" aimed at making personal attacks,

while 39 percent said they were unsure.

Thirty

nine percent of the respondents said they were convinced that the sex

video was a piece of "Umno propaganda" aimed at making personal attacks,

while 39 percent said they were unsure.

Ludwig von Mises Institute – by Andrei Znamenski

Ludwig von Mises Institute – by Andrei Znamenski

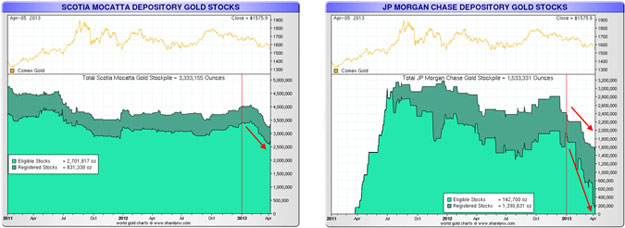

Liberty Gold and Silver

Liberty Gold and Silver

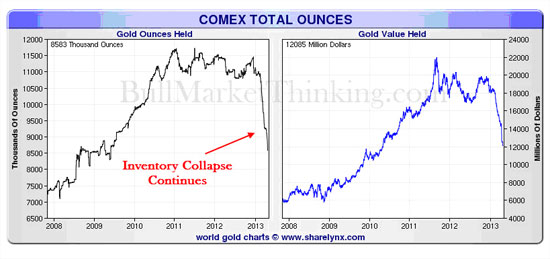

Profit Confidential – by Michael Lombardi, MBA

Profit Confidential – by Michael Lombardi, MBA