STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Saturday marked three years since the Gulf oil disaster erupted

- Since then, Louisiana's statewide oyster catch has dropped by more than 25%

- Other seafood catch numbers have rebounded and studies show the catch is safe

- But in certain areas, there's still a pronounced downturn in blue crab, shrimp, oysters

Yscloskey, Louisiana (CNN) -- On his dock along the banks of Bayou Yscloskey, Darren Stander makes the pelicans dance.

More than a dozen of the

birds have landed or hopped onto the dock, where Stander takes in crabs

and oysters from the fishermen who work the bayou and Lake Borgne at its

mouth. The pelicans rock back and forth, beaks rising and falling, as

he waves a bait fish over their heads.

At least he's got some

company. There's not much else going on at his dock these days. There

used to be two or three people working with him; now he's alone. The

catch that's coming in is light, particularly for crabs.

"Guys running five or six hundred traps are coming in with two to three boxes, if that," said Stander, 26.

Out on the water, the

chains clatter along the railing of George Barisich's boat as he and his

deckhand haul dredges full of oysters onto the deck. As they sort them,

they're looking for signs of "spat": the young oysters that latch onto

reefs and grow into marketable shellfish.

There's the occasional

spat here; there are also a few dead oysters, which make a hollow sound

when tapped with the blunt end of a hatchet.

George Barisich pilots his oyster boat on Bayou Yscloskey, in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana.

John Nowak/CNN

About two-thirds of U.S.

oysters come from the Gulf Coast, the source of about 40% of America's

seafood catch. But in the three years since the drilling rig Deepwater

Horizon blew up and sank about 80 miles south of here, fishermen say

many of the oyster reefs are still barren, and some other commercial

species are harder to find.

"My fellow fishermen who

fish crab and who fish fish, they're feeling the same thing," Barisich

said. "You get a spike in production every now and then, but overall,

it's off. Everybody's down. Everywhere there was dispersed oil and

heavily oiled, the production is down."

Most of the estimated

200 million gallons of oil that poured into the Gulf of Mexico is

believed to have evaporated or been broken down by hydrocarbon-munching

microbes, according to government estimates.

The rest washed ashore

across 1,100 miles of coastline, from the Louisiana barrier islands west

of the Mississippi River to the white sands of the Florida Panhandle. A

still-unknown portion settled on the floor of the Gulf and the inlets

along its coast.

Tar balls are still turning up on the beaches, and a 2012 hurricane blew seemingly fresh oil ashore in Louisiana.

Well owner BP, which is

responsible for the cleanup, says it's still monitoring 165 miles of

shore. The company points to record tourism revenues across the region

and strong post-spill seafood catches as evidence the Gulf is rebounding

from the spill.

But in the fishing communities of southeastern Louisiana, people say that greasy tide is still eating away at their livelihoods.

"Things's changing, and we don't know what's happening yet," said oysterman Byron Encalade.

Life before the spill

Before the spill,

Encalade and his neighbors in the overwhelmingly African-American

community of Pointe a la Hache -- about 25 miles south of Yscloskey --

earned their living from the state-managed oyster grounds off the East

Bank of the Mississippi.

Back then, a boat could head out at dawn and be back at the docks by noon with dozens of 105-pound sacks of oysters.

Now? "Nothing," says Encalade, president of the Louisiana Oystermen Association.

Louisiana conservation

officials have dumped fresh limestone, ground-up shell and crushed

concrete on many of the reefs in a bid to foster new growth.

A piece of brick that was dumped in to the bayou in hopes of reinvigorating the oyster beds.

John Nowak/CNN

It takes three to five

years for a viable reef to develop, so that means Pointe a la Hache

could be looking at 2018 -- eight years after the spill -- before its

lifeblood starts pumping again.

"This economy is totally

gone in my community," said Encalade, 59. "There is no economy. The two

construction jobs that are going on -- the prison and the school -- if

it weren't for those, the grocery store would be closing."

When the catch comes in,

everyone wants you to know that it's safe to eat. Repeated testing has

shown that the traces of hydrocarbons that do come up in the shrimp,

crab and oysters are far below safety limits for human consumption.

"The monitoring of the

seafood supply has been exemplary," said Steve Murawski, a fisheries

biologist at the University of South Florida. "There's no incidence of

people getting sick and no report of any tainted fish reaching the

market."

While much of the Gulf's

seafood industry has rebounded, the hardest-hit communities like Pointe

a la Hache, Yscloskey and the inlets in Barataria Bay, west of the

Mississippi, have not recovered.

Scientists are still trying to understand what the oil has done to the marshlands of southeastern Louisiana.

Both the supply and demand for Gulf oysters have decreased since the pipeline explosion.

John Nowak/CNN

Sure, the catch is safe -- but that doesn't mean much when seafood prices are down and fuel costs are up.

"Since the spill, my

shrimp production is off between 40 and 60% for the two years that I did

work full time," said Barisich, who has both a shrimp boat and an

oyster boat tied up at Yscloskey. "But my price is off another 50%, and

my fuel is high: 60 cents a gallon higher than it's ever been."

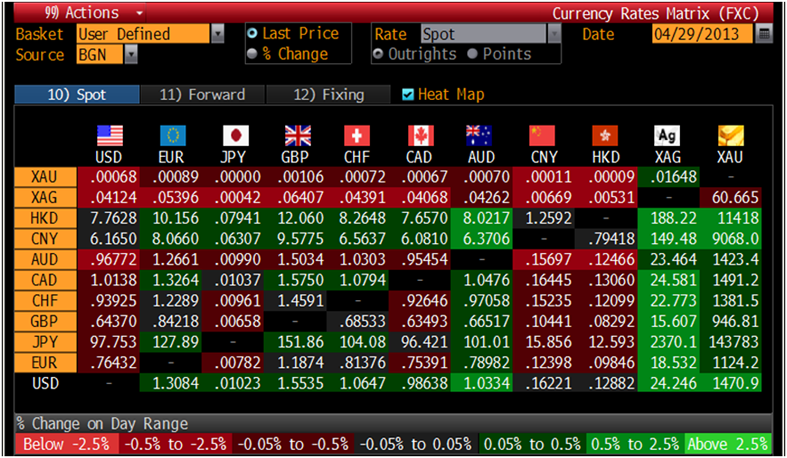

Figures from Louisiana's Department of Wildlife and Fisheries tell a similar story.

The statewide oyster

catch since 2010 is down 27% from the average haul between 2002 and

2009, according to catch statistics from the agency. In the

Pontchartrain Basin, where Encalade and Barisich both work, the

post-spill average fell to about a third of the pre-spill catch.

Barisich says oysters are barely worth the effort anymore.

Guys running five or six hundred traps are coming in with two to three boxes, if that.

Darren Stander

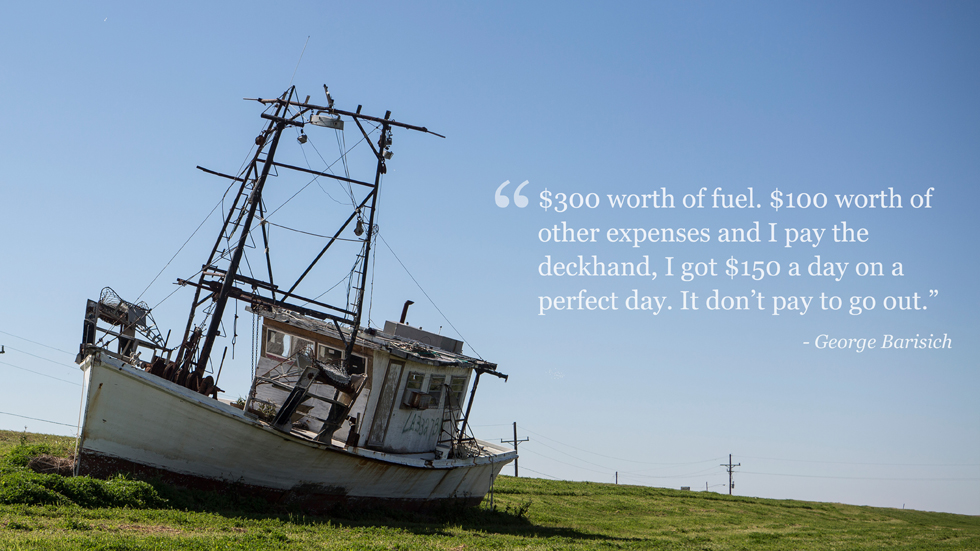

"On the state ground --

on a perfect weather day, keep that in mind -- it's 20 sacks a day," he

said. "Twenty sacks a day at $30 a sack is $600. $300 worth of fuel.

$100 worth of other expenses and I pay the deckhand, I got $150 a day on

a perfect day. It don't pay to go out."

And no boats going out means no fuel being sold at Frank Campo Jr.'s marina, down the bayou from Barisich's dock.

"If you don't burn it, I

can't sell it to you," Campo says. "They're not doing very well with

the crabs, and there's not a lot of oyster boats going out."

Demand for the oysters is off, too.

"You used to never ask

the dealer if he wanted oysters," said Campo, whose grandfather started

the marina. "You just showed up with them. Now, he'll call you and tell

you if he needs 'em."

'Like somebody had poured motor oil all over'

Across the Mississippi

from Pointe a la Hache, beyond the West Bank levees, lie some of the

waterways that saw the heaviest oiling: Barataria Bay and its smaller

inlets, Bay Jimmy and Bay Batiste.

Louisiana State

University entomologist Linda Hooper-Bui tracks the numbers of ants,

wasps, spiders and other bugs at 40 sites in the surrounding marshes, 18

of which had seen some degree of oiling.

She is part of a small

army of researchers who have been trying to figure out what effect the

spill will have on the environment of the Gulf Coast. Since 2010, she's

recorded a sharp decline in several species of insects -- particularly

spiders, ants, wasps and grasshoppers, which sit roughly in the middle

of the food web.

They're top predators among insects but food for birds and fish.

Hooper-Bui said she expected their numbers to bounce back the following year: "Instead, what we saw was worse."

Tar balls found washed up on Elmer's Island, Louisiana, in early March.

John Nowak/CNN

The reason, she

suspects, is that the oil that sank into the bottom of the marsh after

the spill hasn't broken down at the same rate as the crude that floated

to the surface.

Instead, it's in the sediments, still giving off fumes that are killing the insects.

Some napthalenes --

crude oil components most commonly known for their use in mothballs --

appear to have increased since the spill, she said.

"They're volatile, and

they're toxic," Hooper-Bui said. "And they're not just toxic to insects.

They're toxic to fish. They're toxic to birds. They cause eggshell

thinning in birds. We think this is evidence of an emerging problem."

Hooper-Bui said crickets

exposed to the contaminated muck in laboratories die, and when

temperatures were increased to those comparable to a summer day, "the

crickets die faster."

By August 2011, the number of grasshoppers had fallen by 70% to 80% in areas that got oiled.

"By 2012, we were unable to find any colonies of ants in the oiled areas," she said.

Then on August 29, 2012,

Hurricane Isaac hit southeastern Louisiana. The slow-moving storm sat

over Barataria Bay for more than 60 hours as it crawled onto land.

When Hooper-Bui went back to the marshes after the storm, she had a surprise waiting for her.

"We discovered in Bay

Batiste large amounts of what looked like somebody had poured motor oil

all over the marsh there," she said. "About three-quarters of the

perimeter of northern Bay Batiste was covered in this oil."

The chemical fingerprint

of the oil matched the oil from the ruptured BP well, Hooper-Bui said.

Other scientists confirmed that Isaac kicked up tar balls from the spill

as far east as the Alabama-Florida state line, more than 100 miles from

where the storm made its initial landfall.

Far from the shoreline,

patches of oil fell to the bottom of the Gulf in a mix of sediment, dead

plankton and hydrocarbons dubbed "marine snow." It fouled corals near

the wellhead, and it's still sitting there.

There's something about this stuff, the carbon in these layers, that's not degrading.

Samantha Joye, oceanographer

"If you took a picture

of a core (sample) that was collected today and took a picture of a core

that was taken in September 2010, they look the same," University of

Georgia oceanographer Samantha Joye said.

"What's really strange

to me is, the material is not degrading," Joye added. "There's something

about this stuff, the carbon in these layers, that's not degrading."

Normally, microbes go to

work on free-floating hydrocarbons almost immediately, digesting the

compounds. The controversial large-scale use of chemical dispersants was

supposed to accelerate that process by breaking up the oil into smaller

droplets that could be more easily consumed.

But that's not happening to this layer, Joye said, and the reason is unclear.

"The first thing everyone asks is, 'Do you think it's dispersants?' And I can honestly tell you, we don't know," she said.

During the spill,

scientists warned that fish eggs and larvae, shrimp, coral and oysters

were potentially most at risk from the use of dispersants. The

Environmental Protection Agency later reported that testing found the

combination of oil and dispersants to be no more toxic than the oil

alone.

Byron Encalade stands on the dock in Pointe a la Hache, Louisiana.

John Nowak/CNN

But that's no comfort to

Encalade, who could watch planes spray dispersant on the slick from the

marina where he keeps his two boats.

"We know from history,

whenever you put soap in the water around camps and stuff like that,

oysters don't reproduce," he said. "And we've heard BP say over and over

again, 'Oh, it's like detergent.' That's the worst thing in the world

you can do to an oyster."

The impact of these

dispersants on marine life is still an open question, and it's something

that's under review by scientists involved in the

Natural Resource Damage Assessment, the federally run, BP-funded effort to figure out what the spill did to the Gulf Coast.

That assessment could take several years.

As scientists sort out

the data, the Gulf fishing communities from Louisiana to Florida are

still dealing with the impact of the spill. When you look at the entire

expanse of the ocean, there isn't a huge amount of oil, explained Ian

MacDonald, an oceanographer at Florida State University.

"You have to look hard to find any oil at all," he said.

But where the oil has been found, MacDonald said, the damage is "intense and widespread."

There is some good news:

Some studies indicate that commercial fish species in different parts

of the Gulf escaped the worst. Recent research at Alabama's Dauphin

Island Sea Lab found that young shrimp and blue crabs off Bayou La

Batre, the state's major seafood port, showed no sign of decline since

the spill.

But that's no

consolation for Donny Waters, a Pensacola, Florida, fisherman who has

been involved with efforts to rebuild the red snapper populations off

the Florida panhandle.

"I'm still catching

fish. I'm not saying everything's dead," Waters said. "But it's taking

me longer to catch my fish. I'm not seeing the snappers farther around

reefs, whether they're natural or artificial. I'm not seeing the reefs

repopulate nearly as fast since the oil spill."

'BP has retired me'

Like many in the trade,

Encalade and the other guys on his dock in Pointe a la Hache can spin

epic tales. But these days, they're not about the catch. More often,

they're about the red tape and low-ball offers they've had to deal with

in the compensation process set up after the spill -- a process they say

is stacked in favor of big operators.

"I got guys been fishing

out here all their life. They've got trip tickets, more than you can

imagine," Encalade said, referring to the slips that document a boat's

daily catch. "You know what they come back and tell a man his whole life

is worth? $40,000."

The oil, the catch and the money:

All converge at the big federal courthouse on Poydras Street in New Orleans,

where squadrons of lawyers have massed for what promises to be a

protracted brawl to figure out how much BP will end up paying for the

Deepwater Horizon disaster.

BP says it has shelled

out $32 billion for the disaster, including $14 billion for cleanup.

It's also spent $300 million on everything from testing seafood to its

ad campaign that encourages people to come back to the Gulf, and it

pledged $500 million for research into the environmental effects of the

disaster.

The company has paid to

help replace oyster reefs in Mississippi and Louisiana and rebuild sand

dunes and sea turtle habitats in Alabama and northwest Florida. In

addition to monitoring part of the Gulf coastline, BP spokesman Scott

Dean said, the company has planted new grass in the Louisiana marshes,

where the losses sped up erosion already blamed for the loss of an area

the size of Manhattan every year.

But of about 13,000

holes drilled into the beaches and marshes in search of settled oil,

Dean said, only 3% have found enough to require cleanup, he said.

"The vast majority of

the work has been done," Dean said. But when previously undiscovered oil

from the Deepwater Horizon blowout does turn up, "We take

responsibility for the cleanup," he said.

Last year, the company agreed to pay $7.8 billion to individuals and businesses

who filed economic, property and health claims. But in March, the

company asked a judge to halt those payments, arguing that it was facing

hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars in payouts for

"fictitious losses."

It's also pleaded guilty

to manslaughter charges and fined $4 billion in the deaths of the 11

men killed aboard the rig and been temporarily barred from getting new

federal contracts.

George Barisich, left, and his deckhand Bob Caretto separate oysters dredged from Bayou Yscloskey, Louisiana.

John Nowak/CNN

Now BP is back in court,

battling to avoid a finding of gross negligence that would sock it with

penalties up to $4,300 per barrel under the Clean Water Act -- another

$17 billion-plus by the federal government's estimate of the spill. BP

says that figure is at least 20% too high.

The plaintiffs include

the federal government, the states affected by the disaster and people

like Encalade and Barisich, who have rejected previous settlement offers

from BP.

Freddie Duplessis, whose

boat is tied up next to Encalade's, settled with the company. He said

he received about $250,000 from BP after the spill, including money the

company paid to hire his boat for the cleanup effort. That's about what

he says he would have made in six months of fishing before the spill,

before expenses.

I got guys been fishing out here all their life. You know what they come back and tell a man his whole life is worth? $40,000.

Pointe a la Hache oysterman Byron Encalade

"I've been all right.

I've been paying my bills, but what I'm gonna do now?" asked Duplessis,

54. "You're still gonna have bills. Everything I've got is mine, but

I've got to maintain it."

But proving just how

much damage can be blamed on the oil spill will be a difficult task in

the courtroom. That's where the Natural Resource Damage Assessment,

launched after the disaster and partly paid for by BP, comes in. And

right now, the studies that make up that assessment are closely held,

ready to be played like a hole card in poker.

"There's a substantial

amount of fisheries work that's not actually going to see the light of

day until after the court case is resolved," USF's Murawski said.

The region's seafood

landings largely returned to normal in 2011, after the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration closed most of the Gulf to fishing during

the blowout, NOAA data show. And BP notes that across the four states

that saw the most impact -- Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida

-- shrimp and finfish catches were up in 2012 compared with the average

haul between 2007 and 2009.

Blue crab was off about

1%. And while oysters regionwide remained 17% below 2007-09 figures, the

company says that the flooding that hit the region in 2011 has been

blamed for some of that downturn, again by dumping more fresh water into

the coastal estuaries.

And in Louisiana, there's still a pronounced downturn.

State data show that

blue crab landings are off an average of 18%, and brown shrimp -- the

season for which the industry is now gearing up -- is down 39% compared

with the 2002-09 catch.

In Yscloskey, Barisich

said three bayou fishermen took settlements from BP, sold their leases

and walked away from the docks. As for him, at 56, he's trying to adapt.

He's studying for a

license that will allow him to take passengers out on shrimp trawls -- a

kind of working vacation for tourists with a taste for the job he

learned from his father.

"I can't do what I have for the last two years," he said.

And in Pointe a la Hache, Encalade got heartbreaking news in early April.

The public reefs in

nearby Black Bay, one of the post-spill reconstruction projects, had

been closed after spat turned up to protect the larvae. But the spat

died, and the reefs were being reopened to allow the few remaining

mature oysters to be harvested.

"All the little oysters

have died, and the big oysters, you can't make a dollar with them,"

Encalade said. "BP has retired me out of the oyster business."