Inside the lobby of a nondescript building situated in a

strip mall along Eight Mile Road, just outside Detroit, a tall man

emerges from behind a door. Like a nurse calling for a patient at a

doctor's office, he bellows a name.

Attorney David Blanchard stands, picks up his briefcase, and begins to stroll down the hall, past a series of unremarkable offices that double as courtrooms. Beside him is a 50-something woman who works as an information technology specialist. A representative from the woman's employer trails behind.

The woman, who'd prefer to be known as "Sue," is set to meet Administrative Law Judge Raymond Sewell, one of a cast of characters who routinely decides the fate of a parade of people that come through his doors. Sewell and his colleagues take their jobs seriously; they're an affable bunch, which is perhaps surprising, given their line of work: As judges who work for the Michigan Administrative Hearing System, they routinely settle the mundane — tax bills, compensation issues, and disputes over unemployment benefits.

But really, the boring can be earth-shattering for the folks who await their decisions. These administrative law judges dive into hefty problems, giving their cases as much attention as you'd find in the highest courts in the land. They take notes, deliver grand pronouncements, and hand down life-altering decisions.

Sewell's office is decorated with a photo of President Barack Obama and emptiness otherwise. The 78-year-old judge is a former Macomb County prosecutor. He's a lanky gentleman who speaks with a deep, gentle croon.

The reason Sue has taken off work to meet with the judge on an unpleasantly hot and humid day in June is because the state of Michigan believes she's a criminal.

It began like this: In October 2014, Sue filed for unemployment insurance after being laid off from a contracted IT position. Before the economy self-destructed in 2008, she worked at Ford. Today, like many, she relies on contractual employment opportunities. It was the understandable decision to file for unemployment that led her into Sewell's world. According to the state, Sue has misrepresented how much income she earned during periods she claimed to be unemployed.

State records showed she collected a check from the beginning of January 2014 until she was laid off in October.

But that's not the case, according to Sue. It's indisputable when the job began. It was Valentine's Day.

"I remember," she later tells me. "I brought cookies."

Michigan's Unemployment Insurance Agancy is adamant, however, saying its records indicate Sue has received about $2,200 in benefits from the unemployment insurance fund that, according to the agency, she illegally obtained. And because of the alleged fraud, the state says she is required to pay $9,000 in penalties — combined with the $2,200, she's looking at a bill of more than $11,000.

That would freak just about anyone out. And Sue is freaked.

Blanchard, with 10 years of experience handling similar cases, is able to quickly pinpoint an error. For whatever reason, he says, the state's computer system, wrongly, took the lump sum she earned in the first quarter of 2014 (Jan. 1 to March 31), and divided that figure by 13, before spreading the uniform dollar amount across each week.

He hands Sewell a spreadsheet illustrating the error. The representative appearing on behalf of Sue's firm confirms there's no record of her starting work before Feb. 14.

The look on everyone's face in the room presents the same question: What's going on here?

No one from the UIA was present, but Blanchard posits the error is yet another screw-up generated by the UIA's software program used to detect fraud.

Sue appealed the claim, he says, but it fell on deaf ears. Literally.

"[The appeal] was not considered by a human person," says Blanchard.

"You're saying the agency used the computer to determine fraud," Sewell responds.

Yes, without any human oversight, a machine had determined Sue committed fraud. Sewell promptly dismisses the fraud claim, saying Sue was legally entitled to unemployment benefits.

Given those circumstances, some of Sewell's colleagues are baffled by what they've seen lately.

Since 2011, under Republican Gov. Rick Snyder, the state has spent tens of millions of dollars to slowly implement a computer software program that handles applications filed with the UIA. The effort to curb waste is consistent with a vision posed by Snyder of operating government with a business-minded attitude.

The program — called MiDAS — detects possible fraud by claimants.

The problem, says Blanchard, who represents several plaintiffs in a recently filed federal lawsuit that challenges the UIA's alleged "robo-adjudication" system, is that apparent lack of human oversight. MiDAS seeks out discrepancies in claimants' files, according to the lawsuit — and if it finds one, the individuals automatically receive a financial penalty. Then, they're flagged for fraud.

"The system has resulted in countless unemployment insurance claimants being accused of fraud even though they did nothing wrong," the suit says.

The net effect, Blanchard asserts, is that Michigan now has a system in place that criminalizes unemployment. It's a process that, contrary to its stated intention, is creating fraud, rather than eliminating it — a MiDAS touch, if you will, where the state gets the gold: The program has been a windfall for Michigan, collecting over $60 million in just four years.

The state has also gloated about the software's progress in detecting significant amounts of fraudulent claims, but what officials don't seem to grasp is the enormity of the situation, according to administrative judges and attorneys who are routinely involved with fraud cases.

Claimants can be issued a warrant for their arrest, Michigan can garnish their wages and federal and state income taxes, and some succumb to bankruptcy. The number of claimants who have faced those circumstances for being falsely accused of fraud is entirely unknown, but it's clearly an emerging contingent.

That's not to say legitimate claims aren't being brought. But administrative judges, UIA workers, and attorneys say bogus fraud charges are being levied by the state with greater frequency.

So instead of protecting some of the state's most vulnerable residents, they say, the UIA has ushered in a disaster. And those affected by the process, buried in debt, have been pushed to the brink — financially and emotionally. A couple have even attempted suicide in the wake of the "decisions" by MiDAS.

Blanchard says the system is such a mess that he tells people not to apply for unemployment unless their case is a slam dunk.

"People who are clearly eligible are being accused of fraud on a regular basis and it wrecks their lives," he says.

For Sue, the aftershock of being accused of fraud has left an everlasting mark: She never plans to file for unemployment again.

Now, many working-class individuals like her won't either.

'Supports Gov. Snyder's commitment'

The story of Sue and millions across the U.S. should come as no surprise. The economy tanked several years ago and a sharp increase in unemployment applicants followed.

As a result, the Unemployment Insurance Fund — a somewhat complex system that operates off revenue generated by both the state and federal government — began making a significantly higher amount of overpayments to ineligible claimants.

In Michigan, the U.S. Department of Labor found in 2009 that the state's UIA paid an estimated $3.7 billion in unemployment benefits. Of that, the UIA overpaid an estimated 7.2 percent — or $266.4 million, the labor department said.

In 2010, the UIA issued a request to identify technology that could improve the system. Officials said they would tap federal money, generated by the stimulus package approved under Obama for the project, in an attempt to follow suit with the federal government's efforts to curb overpayments.

The ways in which states decided to address unemployment insurance waste varied, according to William Hays Weissman, a shareholder of Littler Mendelson office in Walnut Creek, Calif., who has written extensively on the issue, meaning there wasn't a uniform model to adhere to.

But the desire in Michigan to grapple with UI overpayments attributed to fraud wasn't heightened until Snyder's election in 2010.

In one of his first moves in office, Snyder signed a law that cut Michigan's unemployment benefits from 26 weeks to 20, leading the state to pay "fewer weeks than any other state" at the time, the New York Times observed.

Democrats in the state House and Senate howled, painting the move as an attempt by Republicans to attack the working class and the poor.

But what practically no one realized was that Snyder also greenlighted a bill to purchase software to address unemployment overpayments and fraudulent claims.

A complete overhaul of Michigan's 30-year-old UI system carried a price tag in the tens of millions of dollars.

The Michigan Chamber of Commerce, the largest lobbying group for business in the state, took notice. And it delivered full-fledged support of the endeavor.

Saying the state's UI fund was in a "crisis," a representative from the chamber used the labor department's 2009 figures on overpayment claims — that 7.2 percent of "waste and fraud" — and twisted them to bolster support for the software.

"Based on prior federal data, we know that approximately 30 percent of all overpayments are made to people who were working while fraudulently collecting UI benefits, meaning approximately $143 million was paid to individuals who were working while fraudulently collecting UI benefits in 2009," the chamber executive testified.

That wasn't the truth, however. When the nonpartisan House Fiscal Agency examined the bill, they also addressed the 7.2 percent figure cited by the labor department, and noted only 0.7 percent was attributed to fraud, an estimated $25.9 million.

By implementing new software, "the state may save some unknown portion of those overpayments and fraudulent claims," the HFA concluded in its analysis.

Not exactly inspiring stuff. But with Snyder's signature, the transformation of the Michigan UIA quickly commenced and became a lucrative opportunity for several contractors.

In July 2011, the state awarded Greenwood Village, Colo.-based Fast Enterprises a $47 million contract to begin work on the MiDAS project, a deal officials pegged as a modernization of the state's unemployment insurance infrastructure.

According to the contract, the goals of the MiDAS system were to improve customer service, eliminate manual, labor-intensive process, increase data accuracy, and reduce costs of operations, "specifically in removal of redundant operations, elimination of data errors, detection and elimination of fraud [where possible], and the introduction of streamlined processes."

At the time, the UIA fell under the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA). (Today, it's part of the newly created Department of Talent and Economic Development.) The unemployment system overhaul was meant to align with Snyder's vision for LARA, according to a National Association of State Chief Information Officers award application for MiDAS filed by the state last year. The vision of LARA procured by Snyder, the application notes, is to reinvent government as "customer driven and business minded."

Meanwhile, the UIA awarded an $18 million bid to Chicago-based CSG Government Solutions to provide a "full-time, onsite project management [team] to oversee a comprehensive and complex rewrite of Michigan's current Unemployment Insurance Systems," according to the contract. By September, Michigan purchased the Waterford-based On-Point Technologies case management product for $2 million as a temporary stopgap to "detect and recoup money owed to agencies" until MiDAS was fully operational.

The state also awarded a $14 million contract to SAS Analytics to implement fraud detection software that would be integrated into MiDAS. The purpose was a simple one, SAS wrote in a press release announcing the contract: It will "fight fraud, waste and abuse in the state's unemployment insurance and food stamps program."

Finally, in October 2013, the MiDAS software became fully operational. Its rollout coincided neatly with a reduction in the UIA's staff by roughly one-third. It was a curious decision, especially given the circumstances of the situation: The agency was still bogged down with a mountain of claims stemming from the economic recession.

"While the rollout had its challenges," Fast Enterprises wrote last year, "all-in-all [it] went smoothly — especially when compared to similar rollouts of benefits systems in other jurisdictions."

Supporters of the move said it was the right choice. For years, they said, the Michigan UI system was outdated, generating a backlog of cases and long lines.

But it hasn't been entirely smooth for everyone. The long lines might have disappeared, but they've been replaced by a cascade of computer glitches.

'Whole point' is to prevent hunger, loss of home

There are a few typical reasons why you'll file for unemployment: You've been discharged, laid off, or you quit.

With the implementation of MiDAS, filing now requires you to sign up for the so-called MiWAM Web portal, essentially a website created for claimants to manage their unemployment benefits.

If MiDAS makes a fraud determination, the process has the effect of a steamroller.

First, you'd lose access to a legal advocate — similar to a defender appointed in criminal cases. Michigan is one of few states in the U.S. that provide such a program.

"With that happening, individuals are faced with either going out into the market trying to obtain legal representation," says Anthony Paris, attorney for the Detroit-based Sugar Law Center, which represents claimants in fraud cases and is also an institutional plaintiff in the pending federal lawsuit. "And usually, we're their first call, as far as that goes."

Paris says calls to Sugar Law over alleged fraud claims increased after MiDAS was implemented — and they've skyrocketed ever since the federal complaint was filed in April. The attorney says his office has a list of about 250 individuals who have received questionable fraud allegations from the state over their unemployment benefits. With such an influx of individuals seeking help, the law center's short staff has been bogged down.

The software also retroactively seeks out discrepancies going back six years, Paris says, potentially dredging up fraud charges for individuals who could be on the job again.

Things only get more stressful from there. After a fraud determination has been made, a questionnaire is sent from the UIA. If you don't fill it out — some claimants have missed the notification in their MiWAM account (more on that later) — the state presumes fraud has undoubtedly been committed.

If you do fill it out, and the state still believes you've committed fraud, you have 30 days to appeal, which then can lead you into the courtroom of an administrative judge.

Meanwhile, the state stops paying you unemployment benefits and can immediately start collecting garnished wages and state and federal income taxes.

Attorney David Blanchard stands, picks up his briefcase, and begins to stroll down the hall, past a series of unremarkable offices that double as courtrooms. Beside him is a 50-something woman who works as an information technology specialist. A representative from the woman's employer trails behind.

The woman, who'd prefer to be known as "Sue," is set to meet Administrative Law Judge Raymond Sewell, one of a cast of characters who routinely decides the fate of a parade of people that come through his doors. Sewell and his colleagues take their jobs seriously; they're an affable bunch, which is perhaps surprising, given their line of work: As judges who work for the Michigan Administrative Hearing System, they routinely settle the mundane — tax bills, compensation issues, and disputes over unemployment benefits.

But really, the boring can be earth-shattering for the folks who await their decisions. These administrative law judges dive into hefty problems, giving their cases as much attention as you'd find in the highest courts in the land. They take notes, deliver grand pronouncements, and hand down life-altering decisions.

Sewell's office is decorated with a photo of President Barack Obama and emptiness otherwise. The 78-year-old judge is a former Macomb County prosecutor. He's a lanky gentleman who speaks with a deep, gentle croon.

The reason Sue has taken off work to meet with the judge on an unpleasantly hot and humid day in June is because the state of Michigan believes she's a criminal.

It began like this: In October 2014, Sue filed for unemployment insurance after being laid off from a contracted IT position. Before the economy self-destructed in 2008, she worked at Ford. Today, like many, she relies on contractual employment opportunities. It was the understandable decision to file for unemployment that led her into Sewell's world. According to the state, Sue has misrepresented how much income she earned during periods she claimed to be unemployed.

State records showed she collected a check from the beginning of January 2014 until she was laid off in October.

But that's not the case, according to Sue. It's indisputable when the job began. It was Valentine's Day.

"I remember," she later tells me. "I brought cookies."

Michigan's Unemployment Insurance Agancy is adamant, however, saying its records indicate Sue has received about $2,200 in benefits from the unemployment insurance fund that, according to the agency, she illegally obtained. And because of the alleged fraud, the state says she is required to pay $9,000 in penalties — combined with the $2,200, she's looking at a bill of more than $11,000.

That would freak just about anyone out. And Sue is freaked.

Blanchard, with 10 years of experience handling similar cases, is able to quickly pinpoint an error. For whatever reason, he says, the state's computer system, wrongly, took the lump sum she earned in the first quarter of 2014 (Jan. 1 to March 31), and divided that figure by 13, before spreading the uniform dollar amount across each week.

He hands Sewell a spreadsheet illustrating the error. The representative appearing on behalf of Sue's firm confirms there's no record of her starting work before Feb. 14.

The look on everyone's face in the room presents the same question: What's going on here?

No one from the UIA was present, but Blanchard posits the error is yet another screw-up generated by the UIA's software program used to detect fraud.

Sue appealed the claim, he says, but it fell on deaf ears. Literally.

"[The appeal] was not considered by a human person," says Blanchard.

"You're saying the agency used the computer to determine fraud," Sewell responds.

Yes, without any human oversight, a machine had determined Sue committed fraud. Sewell promptly dismisses the fraud claim, saying Sue was legally entitled to unemployment benefits.

Given those circumstances, some of Sewell's colleagues are baffled by what they've seen lately.

Since 2011, under Republican Gov. Rick Snyder, the state has spent tens of millions of dollars to slowly implement a computer software program that handles applications filed with the UIA. The effort to curb waste is consistent with a vision posed by Snyder of operating government with a business-minded attitude.

The program — called MiDAS — detects possible fraud by claimants.

The problem, says Blanchard, who represents several plaintiffs in a recently filed federal lawsuit that challenges the UIA's alleged "robo-adjudication" system, is that apparent lack of human oversight. MiDAS seeks out discrepancies in claimants' files, according to the lawsuit — and if it finds one, the individuals automatically receive a financial penalty. Then, they're flagged for fraud.

"The system has resulted in countless unemployment insurance claimants being accused of fraud even though they did nothing wrong," the suit says.

The net effect, Blanchard asserts, is that Michigan now has a system in place that criminalizes unemployment. It's a process that, contrary to its stated intention, is creating fraud, rather than eliminating it — a MiDAS touch, if you will, where the state gets the gold: The program has been a windfall for Michigan, collecting over $60 million in just four years.

The state has also gloated about the software's progress in detecting significant amounts of fraudulent claims, but what officials don't seem to grasp is the enormity of the situation, according to administrative judges and attorneys who are routinely involved with fraud cases.

Claimants can be issued a warrant for their arrest, Michigan can garnish their wages and federal and state income taxes, and some succumb to bankruptcy. The number of claimants who have faced those circumstances for being falsely accused of fraud is entirely unknown, but it's clearly an emerging contingent.

That's not to say legitimate claims aren't being brought. But administrative judges, UIA workers, and attorneys say bogus fraud charges are being levied by the state with greater frequency.

So instead of protecting some of the state's most vulnerable residents, they say, the UIA has ushered in a disaster. And those affected by the process, buried in debt, have been pushed to the brink — financially and emotionally. A couple have even attempted suicide in the wake of the "decisions" by MiDAS.

Blanchard says the system is such a mess that he tells people not to apply for unemployment unless their case is a slam dunk.

"People who are clearly eligible are being accused of fraud on a regular basis and it wrecks their lives," he says.

For Sue, the aftershock of being accused of fraud has left an everlasting mark: She never plans to file for unemployment again.

Now, many working-class individuals like her won't either.

'Supports Gov. Snyder's commitment'

The story of Sue and millions across the U.S. should come as no surprise. The economy tanked several years ago and a sharp increase in unemployment applicants followed.

As a result, the Unemployment Insurance Fund — a somewhat complex system that operates off revenue generated by both the state and federal government — began making a significantly higher amount of overpayments to ineligible claimants.

In Michigan, the U.S. Department of Labor found in 2009 that the state's UIA paid an estimated $3.7 billion in unemployment benefits. Of that, the UIA overpaid an estimated 7.2 percent — or $266.4 million, the labor department said.

In 2010, the UIA issued a request to identify technology that could improve the system. Officials said they would tap federal money, generated by the stimulus package approved under Obama for the project, in an attempt to follow suit with the federal government's efforts to curb overpayments.

The ways in which states decided to address unemployment insurance waste varied, according to William Hays Weissman, a shareholder of Littler Mendelson office in Walnut Creek, Calif., who has written extensively on the issue, meaning there wasn't a uniform model to adhere to.

But the desire in Michigan to grapple with UI overpayments attributed to fraud wasn't heightened until Snyder's election in 2010.

In one of his first moves in office, Snyder signed a law that cut Michigan's unemployment benefits from 26 weeks to 20, leading the state to pay "fewer weeks than any other state" at the time, the New York Times observed.

Democrats in the state House and Senate howled, painting the move as an attempt by Republicans to attack the working class and the poor.

But what practically no one realized was that Snyder also greenlighted a bill to purchase software to address unemployment overpayments and fraudulent claims.

A complete overhaul of Michigan's 30-year-old UI system carried a price tag in the tens of millions of dollars.

The Michigan Chamber of Commerce, the largest lobbying group for business in the state, took notice. And it delivered full-fledged support of the endeavor.

Saying the state's UI fund was in a "crisis," a representative from the chamber used the labor department's 2009 figures on overpayment claims — that 7.2 percent of "waste and fraud" — and twisted them to bolster support for the software.

"Based on prior federal data, we know that approximately 30 percent of all overpayments are made to people who were working while fraudulently collecting UI benefits, meaning approximately $143 million was paid to individuals who were working while fraudulently collecting UI benefits in 2009," the chamber executive testified.

That wasn't the truth, however. When the nonpartisan House Fiscal Agency examined the bill, they also addressed the 7.2 percent figure cited by the labor department, and noted only 0.7 percent was attributed to fraud, an estimated $25.9 million.

By implementing new software, "the state may save some unknown portion of those overpayments and fraudulent claims," the HFA concluded in its analysis.

Not exactly inspiring stuff. But with Snyder's signature, the transformation of the Michigan UIA quickly commenced and became a lucrative opportunity for several contractors.

In July 2011, the state awarded Greenwood Village, Colo.-based Fast Enterprises a $47 million contract to begin work on the MiDAS project, a deal officials pegged as a modernization of the state's unemployment insurance infrastructure.

According to the contract, the goals of the MiDAS system were to improve customer service, eliminate manual, labor-intensive process, increase data accuracy, and reduce costs of operations, "specifically in removal of redundant operations, elimination of data errors, detection and elimination of fraud [where possible], and the introduction of streamlined processes."

At the time, the UIA fell under the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA). (Today, it's part of the newly created Department of Talent and Economic Development.) The unemployment system overhaul was meant to align with Snyder's vision for LARA, according to a National Association of State Chief Information Officers award application for MiDAS filed by the state last year. The vision of LARA procured by Snyder, the application notes, is to reinvent government as "customer driven and business minded."

Meanwhile, the UIA awarded an $18 million bid to Chicago-based CSG Government Solutions to provide a "full-time, onsite project management [team] to oversee a comprehensive and complex rewrite of Michigan's current Unemployment Insurance Systems," according to the contract. By September, Michigan purchased the Waterford-based On-Point Technologies case management product for $2 million as a temporary stopgap to "detect and recoup money owed to agencies" until MiDAS was fully operational.

The state also awarded a $14 million contract to SAS Analytics to implement fraud detection software that would be integrated into MiDAS. The purpose was a simple one, SAS wrote in a press release announcing the contract: It will "fight fraud, waste and abuse in the state's unemployment insurance and food stamps program."

Finally, in October 2013, the MiDAS software became fully operational. Its rollout coincided neatly with a reduction in the UIA's staff by roughly one-third. It was a curious decision, especially given the circumstances of the situation: The agency was still bogged down with a mountain of claims stemming from the economic recession.

"While the rollout had its challenges," Fast Enterprises wrote last year, "all-in-all [it] went smoothly — especially when compared to similar rollouts of benefits systems in other jurisdictions."

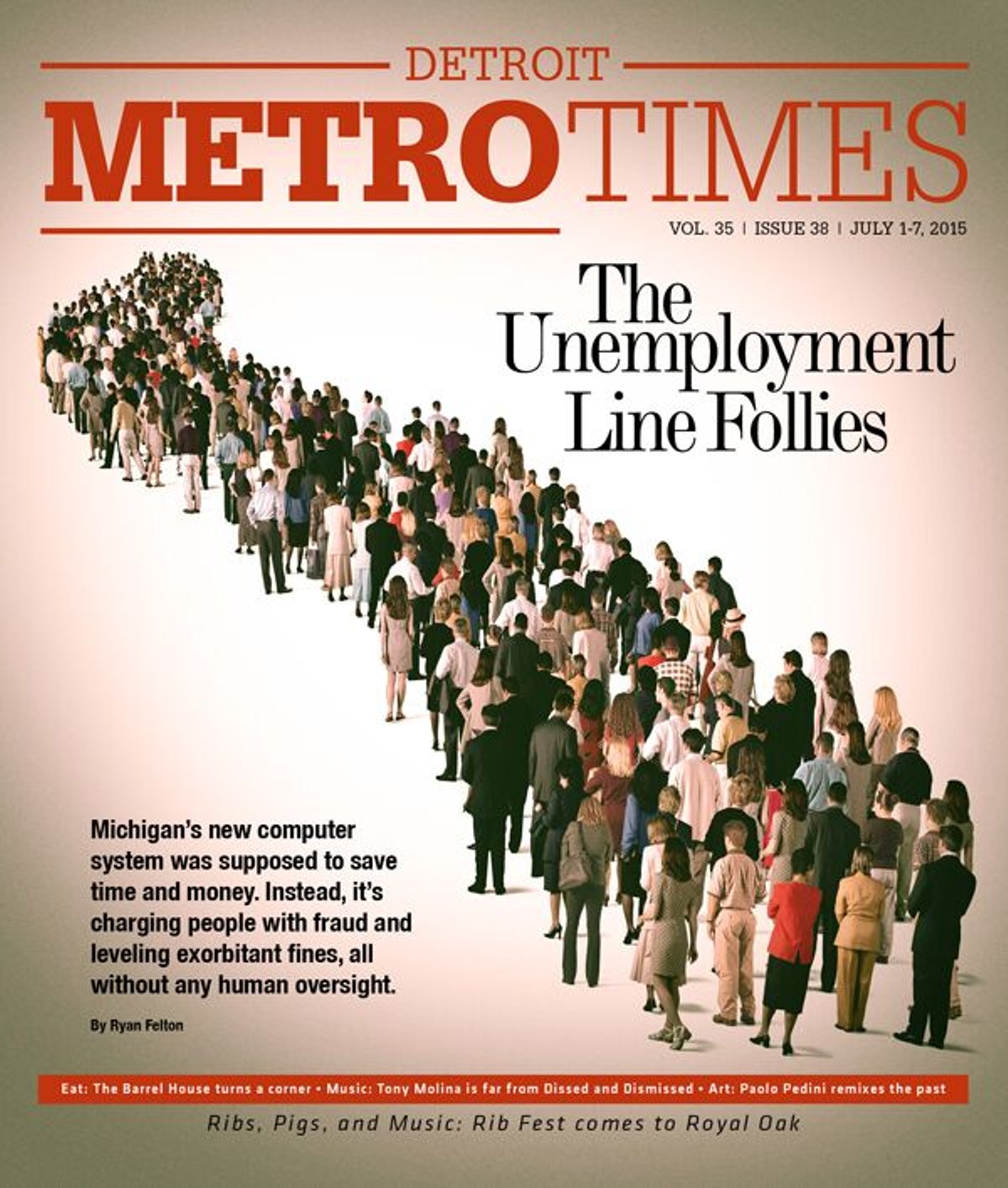

Supporters of the move said it was the right choice. For years, they said, the Michigan UI system was outdated, generating a backlog of cases and long lines.

But it hasn't been entirely smooth for everyone. The long lines might have disappeared, but they've been replaced by a cascade of computer glitches.

'Whole point' is to prevent hunger, loss of home

There are a few typical reasons why you'll file for unemployment: You've been discharged, laid off, or you quit.

With the implementation of MiDAS, filing now requires you to sign up for the so-called MiWAM Web portal, essentially a website created for claimants to manage their unemployment benefits.

If MiDAS makes a fraud determination, the process has the effect of a steamroller.

First, you'd lose access to a legal advocate — similar to a defender appointed in criminal cases. Michigan is one of few states in the U.S. that provide such a program.

"With that happening, individuals are faced with either going out into the market trying to obtain legal representation," says Anthony Paris, attorney for the Detroit-based Sugar Law Center, which represents claimants in fraud cases and is also an institutional plaintiff in the pending federal lawsuit. "And usually, we're their first call, as far as that goes."

Paris says calls to Sugar Law over alleged fraud claims increased after MiDAS was implemented — and they've skyrocketed ever since the federal complaint was filed in April. The attorney says his office has a list of about 250 individuals who have received questionable fraud allegations from the state over their unemployment benefits. With such an influx of individuals seeking help, the law center's short staff has been bogged down.

The software also retroactively seeks out discrepancies going back six years, Paris says, potentially dredging up fraud charges for individuals who could be on the job again.

Things only get more stressful from there. After a fraud determination has been made, a questionnaire is sent from the UIA. If you don't fill it out — some claimants have missed the notification in their MiWAM account (more on that later) — the state presumes fraud has undoubtedly been committed.

If you do fill it out, and the state still believes you've committed fraud, you have 30 days to appeal, which then can lead you into the courtroom of an administrative judge.

Meanwhile, the state stops paying you unemployment benefits and can immediately start collecting garnished wages and state and federal income taxes.

Harry

Harry

The disaster, as you probably already know, was the crisis into which Greece has now plunged.

The disaster, as you probably already know, was the crisis into which Greece has now plunged.