Stanley Fischer did not get a proper vetting at his Senate Banking confirmation hearing last Thursday to serve as Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Of the 22-member Senate Banking Committee, only five Senators, outside of the Chair and Ranking Member, showed up to question Fischer. Questions should have focused on Fischer’s ties to Citigroup, the serially corrupt mega bank which collapsed into the arms of taxpayers in 2008, requiring a bailout of $45 billion in equity infusions, $300 billion in asset guarantees to stop a run on the bank, and over $2 trillion in below market rate loans from the Federal Reserve to prop it up.

Of the five regular Committee members questioning Fischer, all Democrats, only one, Senator Elizabeth Warren, brought up his ties to Citigroup and the bank’s insidious relationship with government and regulators. We’ll get to that in a moment. First, these are the issues on which the public has been denied adequate information and which the Senate Banking Committee has failed miserably to question.

In a December 20, 2001 employment agreement filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on behalf of Citigroup by Sanford (Sandy) Weill, Chairman and CEO, and Robert Rubin, former U.S. Treasury Secretary turned Citigroup Board Member, a new Vice Chairman, Stanley Fischer, would join the bank on February 1, 2002 with a lavish compensation package for a man who had never worked in commercial banking.

In addition to medical and other executive perks, Fischer’s employment agreement promised:

$41,666 in monthly compensation;

A $500,000 “sign-on incentive compensation award”;

A guaranteed bonus of $2 million for 2002, payable in cash and restricted Citigroup stock;

A stock option grant of 75,000 shares of Citigroup common stock, subject to Board approval;

And, finally, the bank would place

$100,000 in the super-secretive Citigroup Employee Fund of Funds I, LP

which lists an address in the Cayman Islands. In addition to fronting

the investment for Fischer, the “contribution will be enhanced with

company-provided two to one leverage.”

By 2004, Fischer was sitting on 188,748 employee stock options according to his SEC filing that year. According to an SEC filing Fischer made

on January 20, 2005, he held a total of 84,791 shares of Citigroup

stock, worth approximately $4.08 million at that time. Wall Street On

Parade was unable to determine just how much Fischer made in profits on

the sale of his stock option awards but it is clear he liquidated or

exchanged them because they do not show on his 2005 filing.Fischer’s employment agreement also contained the same type of caveat that was revealed in the Senate confirmation hearing of Jack Lew, a former Citigroup Chief Operating Officer now serving as U.S. Treasury Secretary. If either Lew or Fischer left Citigroup for a high level position in the U.S. government or a regulatory body, the restricted money Citigroup had put away for them would be theirs to keep.

In Lew’s case, Citigroup, the insolvent ward of the taxpayer, paid Lew $940,000 as a bonus from those taxpayer funds because he joined the U.S. State Department as Deputy Secretary of State under Hillary Clinton, making a few more government hops before landing in his current post as U.S. Treasury Secretary.

Fischer’s employment agreement with Citigroup added a new element: he could also join an “international” governmental body and keep his incentive awards. The agreement read:

“After two years of continuous employment with the Company, in the event that you terminate your employment for purposes of accepting a high level position with a U.S. or international governmental or regulatory body, then your outstanding stock options and restricted stock awards shall vest upon your termination of employment.”

Fischer left Citigroup and immediately became the head of the Bank of Israel, serving in that post until June of last year. But despite the Bank of Israel having a supervisory role over banks operating in the country through its Banking Supervision Department and Citigroup boasting that it has the largest presence of any foreign bank in Israel, Fischer did not exit his Citigroup Employee Fund of Funds I LP in the Cayman Islands.

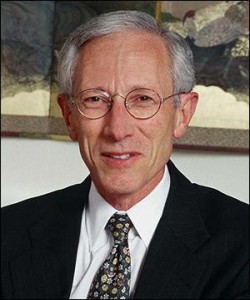

Stanley

Fischer, Former Vice Chairman of Citigroup, Nominated to Serve as Vice

Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors

The Citigroup Employee Fund of Funds I LP is so secretive that on December 31, 2001, the SEC filed a request on behalf of Citigroup in the Federal Register requesting to exempt it and other key employee limited partnership funds at Citigroup from certain provisions of securities laws. The SEC said it was going to approve the exemptions unless someone convinced it to hold a hearing. We could find no information on the SEC’s web site to suggest that the exemptions were not approved or that a hearing was held.

Among the many exemptions requested, Citigroup wanted “to act as custodian for a Partnership without a written contract.” Citigroup asked further for an “exemption from the rule 17f–1(b)(4) requirement that an independent accountant periodically verify the assets held by the custodian.” It also wanted an exemption to be able to keep the partnership’s investments “in the locked files of the General Partner” and to exempt members of the partnership from having to file reports of ownership interests with the SEC.

According to Bloomberg News, Fischer now has a net worth between $14.6 million to $56.3 million, according to his financial disclosure report with the Office of Government Ethics. That’s more than a $40 million spread and a preposterous method of presenting financial disclosures to the public.

On its web site, Citigroup boasts that it has “the largest presence of any foreign financial institution in Israel and offers corporate and investment banking services to leading Israeli corporations and institutions, and global corporations operating in Israel. Citi also offers private banking services to high-net-worth individuals living in Israel.”

Despite it being the U.S. taxpayer that bailed out Citigroup after it played a pivotal role in the economic collapse of 2008, Citigroup’s loyalty to creating jobs to help rebuild the struggling U.S. economy are bizarrely divided. According to its web site, in September 2011, while Fischer served as the head of the Bank of Israel, it established a Technology Innovation Lab in Israel with the aim of capitalizing on “Israel’s vast technological talent to lead the financial industry into the future of technology…The Lab is working on developing an array of state-of-the-art financial and banking applications…Citi has opened a Financial Data Intelligence Lab that will combine expertise in big-data-analytics and domain knowledge within the financial markets.”

While Senator Elizabeth Warren did not get into the nitty-gritty details outlined above, she did frame the core conflicts between Citigroup and the perpetual stream of money men it continues to install in high government positions. That not one other member of the Senate Banking Committee had the guts to go near this subject is further proof of the intractable corruption that plagues Washington.

Senator Warren said:

“Now, I’m concerned that the mega banks

not only have the capacity to tilt the financial system, but that they

also have the capacity to tilt the political system. You know, we’ve

learned that as big banks get bigger and bigger their lobbying power and

influence in Washington also tend to grow. That means big banks can

often delay, water down or even kill important regulations. So, size can

have ripple effects everywhere and for that reason I think it’s a

mistake to talk about size without considering how it affects the

ability of government to enforce meaningful regulation. A century ago

when Teddy Roosevelt and others worked to break up the giant trusts,

this was a big concern – not just the economic impact of size but the

political impact that came with size as well. So, Dr. Fischer, you have a

great deal of experience as an observer and as a participant in the

financial system, is this a point that you’ve thought about and do you

think it’s possible for large Wall Street banks to amass too much

political power?”

Fischer gave a muted response that he wasn’t convinced that banking

supermarkets actually achieve any economies of scale. Warren continued:

“Many big banks are well represented in

Washington but the connection between Citigroup and Democratic

administrations really sticks out. Three of the last four Democratic

Treasury Secretaries have Citigroup ties; the fourth was offered but

turned down the CEO position at Citigroup. Former Directors of the

National Economic Council and the Office of Management and Budget at the

White House and our current U.S. Trade Representative also have

Citigroup ties. You once served as President of Citigroup International

and are now in line to be number two at the Federal Reserve…”

Fischer said he thought his Citigroup experience would help him at the Fed. Warren plowed ahead:

“I also think it’s dangerous if our

government falls under the grip of a tight knit group connected to one

institution. Former colleagues get access through calls and meetings;

economic policy can be dominated by group think; other qualified and

innovative people can be crowded out of top government positions.”

Senator Chuck Schumer Lavishes Praise on Stanley Fischer During Confirmation Hearing on March 13, 2014

As Schumer read his sugary tribute to Fischer, he punctuated his talk with frequent dagger stares in the direction of Senator Warren. By exposing the money men sent from Citigroup, Senator Warren had also, wittingly or unwittingly, pointed the finger at Schumer — their biggest cheerleader in confirmation hearings.

No comments:

Post a Comment