The amount it costs to ship

containers from China to ports around the world has plunged to historic

lows. As container carriers are sinking deeper into trouble, whipped

by lackluster global demand and rampant oversupply of container ships,

they’re escalating a brutal price war with absurd consequences.

Maritime research and advisory firm Drewry (emphasis mine):Recent news stories, backed up by anecdotal stories told to Drewry, report that carriers have quoted zero dollar freight rates to some forwarders on certain lanes out of Asia. Whether these are merely isolated cases or something more widespread is difficult to judge at the present time, but whatever the exact quantum, there is no denying the container rates are now close to the historic lows as seen in 2009.The World Container Index, an average of spot freight rates on 11 global East-West routes connecting Asia, Europe, and the US, plunged last week to a record low of $666 per 40-foot equivalent unit container (FEU), down 73% from mid-2012!

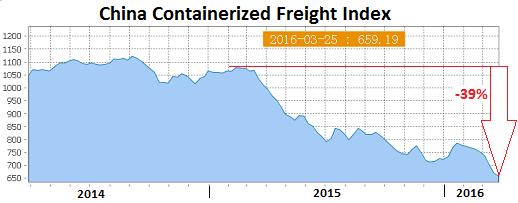

The China Containerized Freight Index (CCFI) tells a similar story. It tracks contractual and spot-market rates for shipping containers from major ports in China to 14 regions around the world. On Friday, the index dropped 1.6% to 659.19, its lowest level ever!

It has plunged 39% from February last year and 34% since its inception in 1998 when it was set at 1,000:

Shippers and their customers are rejoicing for the moment. But the collapse in shipping rates – to “zero” in some cases, as Drewry reported – is taking its toll on the industry.

The risk of carrier bankruptcies – with the awkward side effect of stranded cargo – increases, according to Drewry, “the longer rates remain non-remunerative, while carriers will likely intensify practices such as void sailings in order to minimize the chance of that eventuality.”

In 2009, when shipping nearly came to a halt, carriers relied on other people’s money to keep going:

[C]arriers have a history of shaking off the threat of bankruptcy. In 2009 when the situation was even more precarious than it is now, carriers found ways to survive, calling upon shareholders, governments, and new investors for financial support. Terms with banks, shipyards, and charter owners were renegotiated to limit the immediate cash drain and many needed to sell off assets such as ships, terminals, and some non-core units to repair their balance sheets.But that was the Financial Crisis. It was followed by a V-shaped recovery of shipping volume and freight rates that soon hit new highs. This time, there is no official Financial Crisis. The Fed isn’t engineering any bailouts. The world economy hasn’t come to a standstill, and there won’t be a V-shaped recovery. This will be a long, drawn-out process.

But the first national bailouts are already underway:

While the industry at large has not (yet) reach the same precipice [as in 2009], individual carriers are careering to that point much quicker than others. The most obvious case is South Korean line Hyundai Merchant Marine (HMM).The Korean government is already setting up a $1.2-billion fund to bail out carriers HMM and Hanjin (one of the ten largest by capacity in the world). State-owned Korea Development Bank will also chip in: it agreed, effective March 29, to give HMM a three-month extension of the principal and interest on its debt.

On 17 March bondholders rejected HMM’s debt rescheduling proposal and as of yet there has been no agreement from shipowners to reduce their charter rates in return for equity. The next day HMM Chairwoman Hyun Jeong-Eun resigned her position and a takeover invitation to Hyundai Motors, run by Chung Mong-Koo, who had previously fought for control of HMM, has been rejected, which suggests that government support might be its only hope.

“The most important thing is each company’s possibility of revival,” Oceans and Fisheries Minister Kim Young-suk explained in an interview with The Korean Economic Daily on March 20.

But both would preferably survive as independent companies, he said. “If the companies get merged, file for court receivership, or are sold to a third party, they will be completely dropped out from their global alliances… it would be a huge loss for the Korean shipping industry if we lose one of them that has maintained its hard-won membership.”

So they will be bailed out. Korean taxpayers and some creditors get to eat the losses. Because in the end, there is no “free” ocean freight. And governments around the world are getting ready to shanghai their taxpayers into bailing out their carriers.

Carriers have idled about 1 million TEU (20-foot equivalent unit containers). But they have also put new ships into service, including the new mega-ships with around 19,000 TEU capacity each. And overall industry capacity continues to rise.

But taking a ship out of service for longer periods and then returning it to service is costly, according to Drewry: “In one example, the total bill for a 10,000 TEU ship in six-month cold lay-up (including shutting down most of the ship’s operating systems, repatriating most of the crew and dry-docking) came to just under $1 million.”

A big bet that higher freight rates down the road will make up for these costs. But given the current status of the industry and the global economy, those bets look risky. So far, all of them have backfired. Which leaves Drewry to conclude:

Offering zero freight rates implies a lack of self-regard for their services and an arrogance that they will be bailed out if the worst was to happen.And this would be the next stage of “moral hazard” that was created with such fanfare, beginning in the US and then around the world, via the bailouts during the Financial Crisis.

But this wasn’t part of the rosy scenario. Read… World Trade Collapses in Dollars, Languishes in Volume

No comments:

Post a Comment