Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Companies

image: http://images.intellitxt.com/ast/adTypes/icon1.png

are selling bonds like madmen. This year through Tuesday,

investment-grade and junk-rated companies have sold $438 billion in new

bonds, up 14% from the prior record for this time of the year, set in

2013, according to Dealogic. This quarter is already in second place,

nudging up against the all-time quarterly record of $455 billion of Q2

2014.

are selling bonds like madmen. This year through Tuesday,

investment-grade and junk-rated companies have sold $438 billion in new

bonds, up 14% from the prior record for this time of the year, set in

2013, according to Dealogic. This quarter is already in second place,

nudging up against the all-time quarterly record of $455 billion of Q2

2014.

Brandon Swensen, co-head of U.S. fixed income at RBC Global Asset Management, couldn’t “see anything on the radar that’s going to slow things down materially,” he told the Wall Street Journal. His firm expects rates to “remain low.”

All of the investors chasing after these bonds expect rates to remain low. Or else they wouldn’t chase after these bonds. If rates rise, as the Fed is promising in its convoluted cacophonous manner, these bonds that asset managers

image: http://images.intellitxt.com/ast/adTypes/icon1.png

are devouring at super-high prices and minuscule yields are going to be

bad deals. And their bond funds are going to take a bath.

But companies are selling bonds as if there were no tomorrow. They’re

thinking that rates will not remain low. They’re trying to get these

things out the door cheaply while they still can. They’re on a feverish

mission to take advantage of these ludicrously low rates while they’re

still available. And they use this cheap money to buy each other and to

repurchase their own shares to pump up share prices and max out

executive compensation packages, rather than investing it in productive

activities.

are devouring at super-high prices and minuscule yields are going to be

bad deals. And their bond funds are going to take a bath.

But companies are selling bonds as if there were no tomorrow. They’re

thinking that rates will not remain low. They’re trying to get these

things out the door cheaply while they still can. They’re on a feverish

mission to take advantage of these ludicrously low rates while they’re

still available. And they use this cheap money to buy each other and to

repurchase their own shares to pump up share prices and max out

executive compensation packages, rather than investing it in productive

activities.

So is the Fed giving split signals?

Corporate issuers interpret these signals to mean that this won’t last, that they need to sell as much cheap debt as possible before rates rise, perhaps sharply. But bond fund managers interpret these signals in their own way, lulling themselves into thinking that rates will stay low forever.

One side is misreading the Fed’s signals. Perhaps bond fund managers don’t care; all they have to do is be as good as the market. And when rates go up, the entire market takes a beating, and bond fund managers individually can hide behind that.

But liquidity is a funny thing: it evaporates without notice, just when you need it the most.

Liquidity gives you the ability to sell something without having to slash the price. When no one wants to sell and when you don’t need liquidity, there’s plenty of it. But when you really need liquidity to sell something because you see something worrisome, then everybody else sees the same thing, and they too need to sell. Buyers, who also see the same thing, disappear. And liquidity just evaporates.

It doesn’t mean you can’t sell. It means you have to slash your price to sell. Everyone has to slash their prices in order to lure buyers out of hiding. And worse, as prices get slashed in a highly leveraged market, margin calls go out, hedge funds get nervous, and leverage begets forced selling. And prices drop further. But this leverage once provided liquidity, and now it doesn’t go anywhere else and doesn’t shift to other assets, but gets paid off. It too just evaporates.

That’s the dynamic of market mayhem.

After six years of global QE and interest rate repression, absurdly inflated valuations – from government bonds with negative yields to junk bonds with ultra-low yields – have become the norm. But liquidity has become, to use the Bank of England’s expression, “more fragile.”

Last week, the Bank for International Settlements rang the alarm bells on liquidity, fretting that bond markets have become vulnerable to these sorts of shocks. And yesterday, the Bank of England Financial Policy Committee released the statement of its March 24 meeting that was jam-packed with warnings about “market liquidity risks” – and potential “sharp adjustments in financial markets.”

Not that central-bank warnings have any impact on investors. They’re too busy chasing yield. And thus government bond yields continue to bounce along near zero, or below zero. High-grade corporate bond yields are so small they’re barely discernible. Junk-bond yields show that there are few risks out there, even for the riskiest companies in the riskiest sectors. It has taken central banks six years to blindfold investors to risk, and now investors have become addicted to these blindfolds and simply don’t want to take them off. But when they do, possibly all at the same time, they’ll find out that the liquidity they thought would be there for them has just evaporated.

In the American heartland, real businesses are already getting nervous. “We don’t see the economy being as strong as portrayed in the national media,” the Kansas City Fed quoted one of them. Read… You Should See the Reasons Cited for the Plunge of the Kansas City Fed Manufacturing Index

Companies

image: http://images.intellitxt.com/ast/adTypes/icon1.png

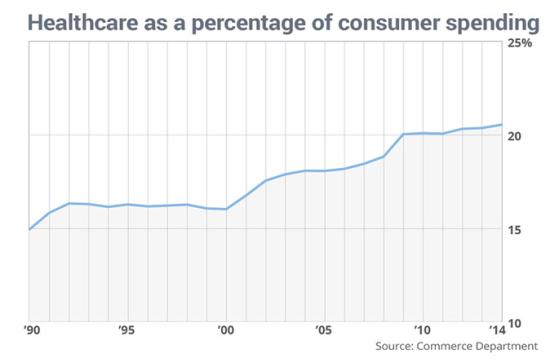

About $87 billion of these bonds funded takeovers, a record for this time of the year, the Wall Street Journal

reported. The four biggest bond sales in that batch were for healthcare

takeovers, including the Actavis deal whose $21 billion bond sale was

the second largest in history, behind Verizon’s $49 billion bond sale in

2013.

Actavis had received orders for more than four times the

bonds available, according to CFO Tessa Hilado. “You don’t really know

what the demand is until people start placing their orders,” she said.

“I would say we were pleasantly surprised.”Brandon Swensen, co-head of U.S. fixed income at RBC Global Asset Management, couldn’t “see anything on the radar that’s going to slow things down materially,” he told the Wall Street Journal. His firm expects rates to “remain low.”

All of the investors chasing after these bonds expect rates to remain low. Or else they wouldn’t chase after these bonds. If rates rise, as the Fed is promising in its convoluted cacophonous manner, these bonds that asset managers

image: http://images.intellitxt.com/ast/adTypes/icon1.png

So is the Fed giving split signals?

Corporate issuers interpret these signals to mean that this won’t last, that they need to sell as much cheap debt as possible before rates rise, perhaps sharply. But bond fund managers interpret these signals in their own way, lulling themselves into thinking that rates will stay low forever.

One side is misreading the Fed’s signals. Perhaps bond fund managers don’t care; all they have to do is be as good as the market. And when rates go up, the entire market takes a beating, and bond fund managers individually can hide behind that.

But what happens when investors in these bond funds

figure out that their bond fund managers had taken the wrong side of

the bet, that corporate issuers had known all along what bond buyers had

closed their eyes to – rising rates falling bond prices – and now

they’re trying to unload their bond funds?

When bond funds face these kinds of redemptions, they first plow

through their cash, then they try to sell the more liquid bonds in their

fund, such as Treasuries, and if that isn’t enough, the less liquid

bonds.But liquidity is a funny thing: it evaporates without notice, just when you need it the most.

Liquidity gives you the ability to sell something without having to slash the price. When no one wants to sell and when you don’t need liquidity, there’s plenty of it. But when you really need liquidity to sell something because you see something worrisome, then everybody else sees the same thing, and they too need to sell. Buyers, who also see the same thing, disappear. And liquidity just evaporates.

It doesn’t mean you can’t sell. It means you have to slash your price to sell. Everyone has to slash their prices in order to lure buyers out of hiding. And worse, as prices get slashed in a highly leveraged market, margin calls go out, hedge funds get nervous, and leverage begets forced selling. And prices drop further. But this leverage once provided liquidity, and now it doesn’t go anywhere else and doesn’t shift to other assets, but gets paid off. It too just evaporates.

That’s the dynamic of market mayhem.

After six years of global QE and interest rate repression, absurdly inflated valuations – from government bonds with negative yields to junk bonds with ultra-low yields – have become the norm. But liquidity has become, to use the Bank of England’s expression, “more fragile.”

Last week, the Bank for International Settlements rang the alarm bells on liquidity, fretting that bond markets have become vulnerable to these sorts of shocks. And yesterday, the Bank of England Financial Policy Committee released the statement of its March 24 meeting that was jam-packed with warnings about “market liquidity risks” – and potential “sharp adjustments in financial markets.”

It cited the Treasury flash crash last October as

an example of when liquidity even in the supposedly most liquid of bond

markets – US Treasuries – just evaporated. As it said, “sudden changes

in market conditions can occur in response to modest news.”

And it frets: “investment allocations and pricing of some securities

may presume that asset sales can be performed in an environment of

continuous market liquidity, although liquidity in some markets may have

become more fragile.”Not that central-bank warnings have any impact on investors. They’re too busy chasing yield. And thus government bond yields continue to bounce along near zero, or below zero. High-grade corporate bond yields are so small they’re barely discernible. Junk-bond yields show that there are few risks out there, even for the riskiest companies in the riskiest sectors. It has taken central banks six years to blindfold investors to risk, and now investors have become addicted to these blindfolds and simply don’t want to take them off. But when they do, possibly all at the same time, they’ll find out that the liquidity they thought would be there for them has just evaporated.

In the American heartland, real businesses are already getting nervous. “We don’t see the economy being as strong as portrayed in the national media,” the Kansas City Fed quoted one of them. Read… You Should See the Reasons Cited for the Plunge of the Kansas City Fed Manufacturing Index